In this paper, I will use a western theory of parody to analyze some parodic dimensions of late Heian‒Kamakura court literature. The Heian period is usually dated from 794 to 1185 and the Kamakura period from 1185 to 1333. The works discussed in this paper were written between the (late) 11th and 13th centuries. However, I do not presume that Western theories could be applied to ancient Japanese works uncritically, but instead, I will explore the possibilities these theories can offer for interpreting medieval Japanese court literature.

I will focus on allusions to Genji monogatari in late Heian and Kamakura monogatari.1 Since Genji monogatari was written around the year 1008, it has inspired an enourmous number of other cultural products. Some scholars, such as Masako Mitamura, have especially emphasized the importance of Genji monogatari as a so-called “holy classic” (koten no seiten) from the late Heian‒Kamakura period onwards.2 On the other hand, Genji monogatari has inspired a number of pastiches and parodies. Parodies from the Edo period (from 1600 to 1868), such as Nise murasaki inaka Genji 3 , are well-known, but in this study I would like to concentrate on earlier reformulations of Genji and discuss their parodic aspects.

Ridicule or not? Reconsidering the concept of parody

Instead of fixing a rigid definition for parody beforehand, I prefer to analyze different imitation modes and discuss their possibilities as parodical discourses.

As Tzvetana Kristeva has pointed out in his article Parodi no riron to Nihon bunka, instead of “adopting”modern Western literary theories, we should “adapt” them to the context of Japanese literature4. The parodic discourses on Japanese literature are often described in terms of concepts such as modoki and mojiri, but they seem to refer to very different kinds of phenomena. Parodies on the level of style and expression are more rare in Western literature, whereas mojiri, chakkashi and other forms of parody in Japanese literature are constructed merely through alteration of expression.

The processes of imitation and citation have been essential parts of Japanese culture since ancient times and especially during the Japanese Middle Ages. However, as Kuniaki Mitaki states, despite numerous terms referring to parody (such as modokiもどき, maneまね, mojiriもぢり, yojirizurashiよぢりずらし, kaheかへ, okoをこ, warahi わらひ, kokkei滑稽, fūshi風刺, mohō模倣, choshō 嘲笑), there seems to be no satisfying equivalent for the word “parody” in Japanese.5 Therefore, I shall apply a Western theory that provides a useful tool for my analysis.

My research has been inspired by the concept of parody presented by Linda Hutcheon. Her theory is especially attractive for its perspective on the role of irony and the question of whether humour is an essential aspect in parody. Hutcheon’s theory was created on the basis of 20th century art forms. However, it is important to note that Hutcheon herself does not offer any universal definition for parody, arguing that it should be always defined in a historical and cultural context.6

In her book A theory of parody Linda Hutcheon has extended the classical definition of parody by taking the etymological root of the Greek noun parodia meaning “counter-song” as a point of departure. While para is usually translated as “counter” or “against”, she points out that para in classical Greek can also mean “beside” and thus suggest accord or intimacy rather than contrast. “There is nothing in parodia that necessitates the inclusion of a concept of ridicule (…)”, Hutcheon states. Parody is thus about ironic “trans-contextualization” and inversion, repetition with difference.7

According to Hutcheon, in parody there is in the background “another text against which the new creation is implicitly to be both measured and understood”. In her opinion, the so-called “modern form” of parody “does not always permit one of the texts to fare any better or worse than the other.” Rather the difference between two texts is emphasized and dramatized. Irony is the essential “rhetorical mechanism for activating the reader’s awareness of this dramatization”, Hutcheon argues.8

Hutcheon’s theory was later criticized by Margaret Rose, among others.9) Especially the question of whether humor is essential in parody has been debated by many authors. However, in my view, ridicule does not necessarily have to be highlighted in parody. This theory is enlightening because it emphasizes the role of irony in parody.

I have selected examples that demonstrate what kind of textual phenomena the concept of parody could possibly cover. Before that, I shall briefly discuss the role of Genji monogatari during the late Heian‒Kamakura period.

The Role of Genji and its parodic dimensions in Heian‒Kamakura literature

An enormous number of intertextual links to earlier literature prove that what we call intertextuality was a necessary format of literary expression for late-Heian‒Kamakura literary spheres. Rhetorical devices, such as honkadori (borrowing words and phrases from older poems) in poetry and honzetsu (borrowing words and phrases from earlier prose works) in prose provided tools for the deconstruction and re-interpretation of earlier works. It goes without saying that not all of these allusions contain parody, and therefore the question of interpretation becomes essential.

In contrast to the well-known examples of parodies that were produced during the Edo period among the common people, the parody of medieval court literature was produced and consumed by a small circle of readers, all of whom would have shared the same basic knowledge of classical literature. Therefore, while the parody of the Edo period can still be easily recognized by modern readers as well, the parodic nature of court fiction is more subtle, requiring a considerable amount of knowledge of earlier works and the style of the genre in question.

In order to be able to interpret medieval monogatari, one should also reflect on the implicit rules that restricted the act of writing in Heian‒Kamakura court society. For example, ordinary things, such as eating, are rarely described. The general subject of monogatari consists of various love affairs and usually forbidden relationships. Still, for the sake of style, sexuality is expressed in a very refined manner. At the same time, however, topics such as homosexuality and cross-dressing clearly were not taboo.

Undeniably, Genji monogatari’s role as a representative work of Heian literature and court culture cannot be underestimated. The symbolic value of Genji as a representative of the much idealized heyday of Heian culture was considerable for the later nobility, who were losing political power to the military class. This phase of reception occurred mainly in aristocratic society and imperial court. Many readers and writers were aristocratic women, to whom monogatari (tale literature) was the most popular pastime reading material. Thus, this first-hand audience was highly educated and well aware of literary conventions of the time.

However, I would like to emphasize that Genji monogatari performed an ambivalent function in the court spheres of the late Heian‒Kamakura nobility. On the one hand, there was an apparently serious effort to promote Genji as a representative of the glorious Heian past.

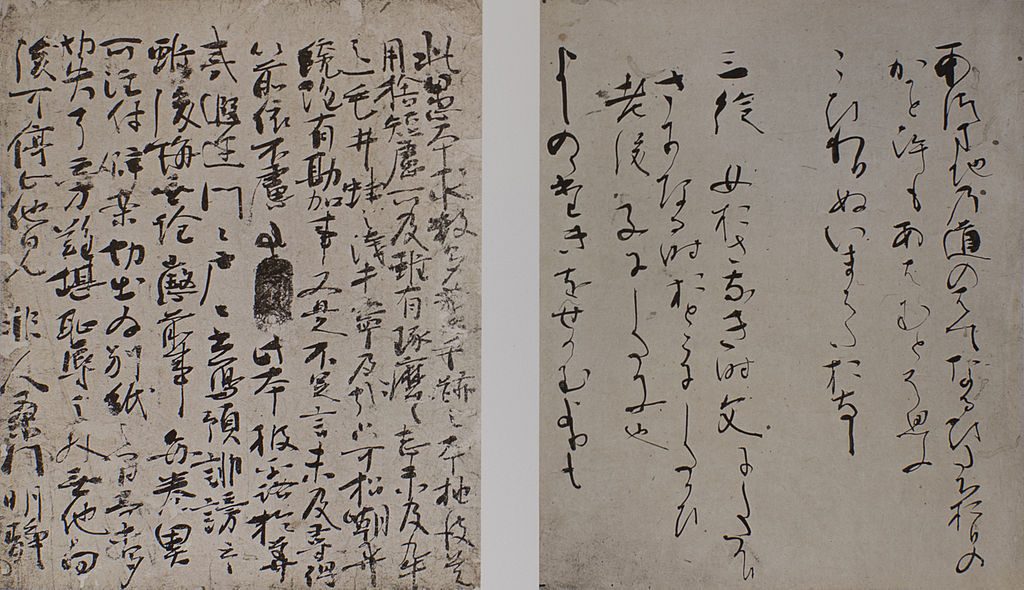

On the other hand, especially in private spheres, the same work was a source for playful amusement. Moreover, these two aspects cannot always be separated from each other ‒ as can be seen, for instance, in the afterword (batsubun) of Kōan Genji rongi, the first annotation in Genji monogatari. The work was collected on the basis of a nominally formal debate in 1280 at the court of the crown prince (the later emperor Fujimi), as it was recorded by Minamoto no Tomoaki (1260?-1287). This partly ludic event cannot be estimated as literature research , but it shows how intimate a relation the nobles had towards Genji monogatari This extract contains elements of parody of Kokinwakashū(an imperial poetical anthology collected in the early 10th century) à la Genji monogatari.

光源氏は。式部が心を種として。よろづのことの葉とぞなれりける。よの中にある人ことわざしげきものなれば。こゝろにおもふことを。見る物きくものにつけてよそへいへるなり。花にすまぬはこ鳥。山になく鹿のこゑをきくまでも。いきとしいけるもの。いづれかこれをのせざりける。(・・・)この物語。ひろくひろき年のほどよりもいできにけり。(・・・)

『群書類従』「弘安源氏論議」10

The seeds of Hikaru Genji lie in the heart of Murasaki Shikibu and grow into leaves of ten thousand words. Many things happen to the people of this world, and all that they think and feel is told to others in description of things they see and hear. When we hear the cuckoo living in the blossoms or the voice of the deer in the mountains, which of all the creatures of this world would not write it down? This monogatari spread widely from many years earlier. 11

As was clear to contemporary readers from the first few words, this is clearly an imitation of the preface of Kokinwakashū (the so-called kanajo or kana preface, written in kana syllables by one of the compilers, Ki no Tsurayuki), resembling a form of parody of the Edo period called mojiri. For comparison, here is what kanajo says:

やまとうたは、人の心を種として、よろづの言の葉とぞなれりける。世の中にある人、ことわざしげきものなれば、心に思ふことを、見るもの聞くものにつけて、言ひ出 せるなり。花に鳴く鶯、水に住むかはづの声を聞けば、生きとし生けるもの、いづれか歌をよまざりける。(・・・) この歌、天地の開け始まりける時より出で来にけり。(・・・)12

The seeds of Japanese poetry lie in the human heart and grow into leaves of ten thousand words. Many things happen to the people of this world, and all that they think and feel is given expression in description of things they see and hear. When we hear the warbling of the mountain thrush in the blossoms or the voice of the frog in the water, we know every living being has its song.13

Interestingly, it shows that not only the ultimate classic of the monogatari but also the most important imperial anthology could be rewritten as parodic amusement, even though it was part of an (at least nominally) official work. The humorous shades are light, but it is clear that the readers were amused in recognizing the well-known wording by Tsurayuki, here associated to Murasaki Shikibu, the court woman who is commonly known as the author of (at least most of) Genji monogatari. Kōan genji rongi is also remarkable because the debate was realized by male participants only, hence indicating change in the reception history of Genji monogatari. Eight participants were divided into two teams of four, to discuss 16 topics in the form of dialogue (mondō 問答) or a poetic competition (uta awase 歌合), commented on by a judge who decided who won.

On the basis of Kōan genji rongi, it can be supposed that Genji monogatari became widely read around 1077‒1103, and during the 12th century the work was illustrated, while various legends about Murasaki Shikibu and Genji monogatari were born. Soon, the first commentaries, such as Genji shaku (1175) had become indispensable.14

On a more general level, I argue that the nature of these literary allusions (in late Heian‒Kamakura court literature) was often not simply allusive, but the medieval texts were commenting on and re-contextualizing works like Genji monogatari more frequently than has usually been pointed out. As Hutcheon expresses it, “Parody, therefore, is a form of imitation, but imitation characterized by ironic inversion, not always at the expense of the parodied text”15. In my view, Hutcheon’s theory provides us with a useful tool for understanding some of the mechanisms of medieval Japanese imitation and parody.

In other words, I think that this so-called ironic attitude often seems to originate from the consciousness of the gap between the idealized fictive world and the reality experienced by the authors and readers.

Meanwhile, the multi-layered relationship between texts is often much more complicated than simple parody. As I see it, parodical passages appear sporadically so this phenomenon is limited to certain part(s) of a narrative rather than covering the whole work.

In this paper I argue that rather than “a model text”, Genji had become a common source of material to be used and re-used when writing a monogatari (not necessarily one’s own Genji), and that literary criticism was part of this process. Consequently “critical distance” and “repetition with difference” were necessary components in the creation of new monogatari. Furthermore, ironic attitude seems to be much more common in the post-Genji tales than usually recognized.

As Charo B. D’Etcheverry has mentioned, part of the success of Genji stems from their creative usage of it, not only borrowing Genji-like features (such as characters) but also reinterpretating or questioning their source. The reevaluation of late Heian and medieval monogatari shows that these tales deliberately comment on Genji and the society that produced it. D’Etcheverry has analyzed the Tales of Sagoromo, Nezame and Hamamatsu in order to show how these tales typically do this by “creating simplified versions of a favorite Genji motif or storyline, forcing readers to confront Murasaki’s less obvious insights about court life and then expanding on the subject”.16

We can say that during the late Heian‒Kamakura period the poetic tradition was reevaluated using rhetorical means based on intertextuality ‒ such as honkadori (technic of “borrowing” part of an older waka poem). In my view, the same kind of reevaluation also took place in prose; a reevaluation in which the most adored classics were subverted and imitated: the best-known scenes and characters could even form “patterns” that contained reinterpretations of the original scene.

As some scholars, such as Fukuda Hideichi,17 have pointed out, the influence of Genji on later literature is by no means limited to direct intertextuality, but can be seen on various levels.

In my view, we can separate at least these four levels of influence:

- “direct” (textual) intertextuality (words, phrases, grammatical structure, vocabulary)

- imitation of a scene (a character acts in a way that resembles that of a character in Genji)

- imitation of a character’s characteristic features or relationship between characters in Genji

- the characters deliberately act in a similar way as in Genji and the influence is explicitly pointed out.

The Story of Murasaki no Ue reconstructed

As an example, I demonstrate how the story of one of the heroines, the young Murasaki no Ue, abducted by Hikaru Genji, was imitated in later literature.

わらはやみにわづらひ給ひて、よろづにまじなひ加持などまゐらせ給へど、しるしなくて、あまたゞびおこり給ひければ、ある人、「北山になむ、なにがし寺といふ所にかしこき行ひ人はべる。こぞの夏も世におこりて、人々まじなひわづららしを、やがてとゞむるたぐひあまた侍りき。しゝこらかしつる時は、うたて侍るを、とくこそこゝみさせ給はめ」など聞こゆれば、(一五一頁)

中に、十ばかりにやあらむと見えて、白き衣、山吹などのなれたる着て、走り来たる女ご、あまた見えつる子供に似るべうもあらず、いみじく生ひ先見えて、美しげなるかたちなり。髪は、扇を広げたるやうに、ゆら/\として、顔はいと赤くすりなし立てり。(一五六頁)

つらつきいとらうたげにて、眉のわたりうちけぶり、いはけなくかいやりたる額つき、かんざし、いみじううつくし。ねびゆかむさまゆかしき人かなと目とまり給ふ。さるは、限りなう心をつくし聞ゆる人に、いとやう似奉れるがまもらるゝなりけり、と思ふにも、涙ぞ落つる。(一五七頁)

『源氏物語』「若紫」18

Genji, who was suffering from a recurrent fever, had all sorts of spells cast and healing rites done, but to no avail, the fever kept returning. Someone then said, “My lord, there is a remarkable ascetic at a Temple in the Northern Hills. Last summer, when the fever was widespread and spells failed to help, he healed many people immediately. Please try him soon. (p. 83)

In among them came running a girl of ten or so, wearing a softly rumpled kerria rose layering over a white gown and, unlike the other children, an obvious future beauty. Her hair cascaded like a spread fan behind her as she stood there, her face red from crying. (p. 86)

She had a very dear face, and the faint arc of her eyebrows, the forehead from which she had childishly swept back the hair, and the hairline itself were extremely pretty. She is one I would like to see when she grows up! Genji thought, fascinated. Indeed, he wept when he realized that it was her close resemblance to the lady who claimed all his heart that made it impossible for him to take his eyes off her. (p. 86‒87)19

In this narrative of Genji monogatari, the so-called proto-text in question, the protagonist Hikaru Genji, , is suffering from some sort of illness, warawa yami.20 It has been suggested21 that this opening already possibly refers to Genji’s fixation on his steph-mother, Fujitsubo Consort.

As the usual prayers and incantations do not provide relief, Genji goes to a certain temple in the northern hills (Kitayama), to meet a sage (sagashi hito, hijiri) who is known for curing ills. Eventually, the protagonist discovers a dwelling where he espies an old nun and a young girl, later known as Murasaki, who fascinates him.

The story continues, and finally Genji ends up taking the girl with him and hiding her in his villa. The chapter closes with Murasaki trying to come to terms with her new situation. Finally she is raised by Genji and is married to him.

As has been pointed out several times, young Murasaki is associated with Genji’s stepmother Fujitsubo from the very beginning, as a kind of substitute (yukari) for her. Genji immediately recognizes the girl’s resemblance to his stepmother. Later, he is delighted to discover that Fujitsubo is actually Murasaki’s aunt. It has also been argued that the scene in question is alluding to the beginning of Ise monogatari where the protagonist experiences his first love (hatsu koi).22 I will return to these two points later.

Unplucked eyebrows and white teeth

Kaimami (the act of peeping at a lady) and the abduction of a lady is one of the popular plot patterns in post-Genji monogatari, and the story of Murasaki may be one of the most adapted story lines of Genji. Consequently, it appears to be prone to parodic renderings. However, we should also keep in mind that Genji’s influence is often seen on other narrative levels as well, such as the relationship between the characters.

In Mushi Mezuru Himegimi, a late Heian story from the collection of short stories of Tsutsumi chūnagon monogatari, Murasaki’s story is evoked by the description of the uncultivated (or unladylike) appearance of the protagonist, “The Lady-who-admired-vermin”. Her unkempt hair, (tsukurohanu kami) and unplucked eyebrows (mayu sara ni nuki tamahazu) make her resemble a young girl and thus remind the reader of the unaffected charm of young Murasaki.

The lady’s hair remains untended and her eyebrows are unplucked. Contrary to custom, she refuses to blacken her teeth, proclaiming that using the tooth-blackening dye (hagurome) is bothersome and untidy (sarani urusashi, kitanashi). Her behaviour is thus unthinkable with regard to contemporary aesthetic ideals. When she laughs, she shows her non-blackened white teeth (ito shirakani warami tsutsu) 23 Her movements, described by verbs such as “to step” (fumu) and “to run” (hashiru24) are not suitable for a lady.25 In fact, she moves like a child, running and jumping in a way that is not appropriate for a young noble lady but instead resembles young Murasaki. Like Murasaki, she is dressed in a white hakama, even though adult women usually wore red ones.26

「人はすべて、つくろふところあるはわろし」とて、眉さらに抜きたまはず、歯黒め、「さらにうるさし、きたなし」とて、つけたまはず、いと白らかに笑みつつ、この虫どもを、朝夕べに愛したまふ。人々おぢわびて逃ぐれば、その御方は、いとあやしくなむののしりける。(六四頁)

「・・・ただここもと、御覧ぜよ」と言へば、あららかに踏みて出づ。(八五頁)

練色の、綾の綾の袿ひとかさね、はたおりめの小袿ひとかさね、白き袴を好みて着たまへり。

(八五頁)

『堤中納言物語』「虫めづる姫君」27

“As a rule it is wrong for people to make themselves up,” she would say, and never plucked her eyebrows, and never applied tooth blackening because she thought it was bothersome and dirty. And she doted on the vermin from morning till night, all the while showing the gleaming white of her teeth in a smile. Whenever people fled from her in consternation, this “lady” would shout at them in a very peculiar manner (p. 55).

”Would you just come and look at them here?” At that she trod brusquely into the open (p. 63).

She wore robes of figured silk in pale yellow under an outer robe with katydid design, and preferred her trousers white (p. 63).

One of the servants, “a faultfinding woman” (togatogashiki onna), defends the protagonist in the following manner:

「・・・また、蝶はとらふれば、瘧病せさす なり。あな、ゆゆしともゆゆし」と言ふに・・・ (七二頁)

『堤中納言物語』「虫めづる姫君」

“Also, they say that if you catch a butterfly, it gives you the ague. Horrid things!” (p. 57)28

In other words, the description of the lady in question is far too striking to be taken seriously; it is intended to amuse the reader. In my view, this short story could also have been understood as a parody of Hikaru Genji and Murasaki no Ue’s relationship. Some scholars, such as Mitani Kuniaki29 and Shimotori Tomoyo30 have also pointed out the connection of Mushi mezuru with the Waka Murasaki chapter.

In terms of vocabulary, there are certain common “keywords” shared by both texts (Genji and Tsutsumi), such as warawa yami (Genji’s sickness) and mayu (eyebrows), as well as the description of the protagonist’s appearance. The mention of the sickness of warawa yami (p. 44), for instance, by the attendant who is defending the young lady, may refer to Wakamurasaki, where young Hikaru Genji is retiring to Higashiyama to meet an esoteric (hijiri) in order to cure his warawa yami. The fact that the name of this particular disease is mentioned in the narrative shortly after the description of the lady’s peculiar appearance, fortifies the impression of a “hint” to the intertextual link, stressing the presence of the proto-text. The term warawa yami appears very rarely in Japanese classical literature.31 The use of such a rare and special expression appears to be deliberate.

The word mayu (eyebrows) is also very rarely used in Genji monogatari, but is mentioned two times in the description of young Murasaki, possibly emphasizing her childlike appearance because her brows have not yet been plucked.

In the chapter Suetsumu hana, there is this description of Murasaki:

古代の祖母君の御名残にて、歯ぐろめまだしかりけるを、引き繕はせ給へれば、眉のけざやかになりたるも、うつくしう清らなり。(四六、四七頁)

『源氏物語』末摘花32

In deference to her grandmother’s old-fashioned manners, her teeth had not yet received any blacking, but he had had her made up, and the sharp line of her eyebrows was very attractive. (p. 130)

In the chapter Waka Murasaki, the old nun admires what beautiful hair the girl has although she refuses to have it combed.

尼君、髪をかき撫でつゝ、「けづる事をもうるさがり給へど、をかしの御ぐしや。(一五七頁)

『源氏物語』若紫33

“You hate even to have it combed,” the nun said, stroking the girl’s hair, “but what beautiful hair it is!” (p. 87).34)

The non-blackened teeth and unplucked eyebrows are here described as beautiful and charming. In Mushi mezuru, the lady is said to have hair that falls beautifully, though messily from not being combed. Her mouth is described as being attractively formed and pretty, but looking unconventional since she has not applied tooth blackening.

髪もさがりば清げにはあれど、けづりつくろははねばにや、しぶげにみゆるを、眉いと黒く、はなばなとあざやかに、涼しげに見えたり。口つきも愛敬づきて、清げなれど、歯くろめつけねば、いと世づかず。(八五頁)

『堤中納言物語』「虫めづる姫君」35

… and her hair, though the sidelocks made a pretty curve downward, had a prickly look about it, perhaps because she did not groom it, while her eyebrows stood out very dark in gaudy relief and looked crisp. Her mouth was attractively formed and pretty, but since she did not apply tooth blackening, it was most unconventional (p. 63).

This description invites us to ask if the “realism” that occurs in the story could be one of the methods of parody: usually the faces of the heroine (or hero) would not be described in detail.The description would rather focus on brilliant and colorful clothes, shining hair, or the ability to play various instruments or to write poems, and so on. It was out of the question to describe the heroine’s teeth or eyebrows, since it went without saying that eyebrows were properly plucked and teeth blackened. The realistic descriptions of the abnormality of these features must have seemed almost disgusting to contemporary readers. While the modern reader would likely feel sympathetic towards the heroine, with her preference for reality over illusion, for the natural over the artificial, cultural artefacts must be interpreted by the standards of their own culture and not those of ours.

At the very beginning of the tale, the protagonist is contrasted to the “lady-who-admired-butterflies” who is said to live nearby. The lady who loves butterflies is mentioned only twice, as an example of correct social behaviour in contrast to the protagonist. While she never appears in the story herself, she is nonetheless crucial to its development since the polarization of the two ladies is a very important aspect of the narrative, and in fact it accentuates the parodic features of the story.

蝶めづる姫君の住みたまふかきたはらに、按察使の大納言の御むすめ、心にくくなべてならぬさまに、親たちかしづきたまふことかぎりなし。

『堤中納言物語』「虫めづる姫君」36

Next to the place where lived the lady who admired butterflies was the daughter of the Inspector Grand Counselor, whose parents tended her with such infinite care that she grew up to be a creature of intriguing and exceptional beauty (p. 53).37

The only function of mentioning the lady next-door is to emphasize the apparent difference between the two ladies – one expressing affections that were suitable for the contemporary noble woman, the other having unthinkable hobbies. Discovering these signs, the reader is able to decode the lady loving insects38 (and in particular, caterpillars) as a parodic caricature of a noblewoman of the Heian period. In this aspect, the minor role of the lady next-door (never appearing in the story herself) is crucial, as she represents a stereotypical heroine of monogatari.39

As Higashihara Akinobu has argued, adult-like behaviour and socially acceptable gender roles are thus associated with butterflies while the childlike protagonist is associated with caterpillars. The caterpillar-lady is refusing to behave as an adult female should. Just like Murasaki, she is still a “caterpillar” that should be transformed into a butterfly.40 Furthermore, the lady’s servants, who are mocking her, associate her unplucked eyebrows (mayu) with furry caterpillars and her white teeth with those who have been peeled of their skin. Uma no suke’s waka also associates furry caterpillars with the lady’s unplucked eyebrows (mayu).

As has been pointed out several times, this short story apparently is a humorous example of kaimami episodes, where a gentleman (irogonomi) is peeping at a lady. The best-known kaimami scene is the first chapter (dan) of Ise monogatari, where the protagonist peeps at two sisters (or only at one lady, depending on the interpretation). Interestingly, many scholars (such as Ii Haruki41 and Shimotori Tomoyo42 ) have pointed out that this famous scene of Ise monogatari is evoked in the kaimami of Hikaru Genji. Higashihara Nobuaki, among others, has even argued that the Wakamurasaki episode is actually a parody of the first chapter of Ise.

Higashihara has analyzed Mushi mezuru as a parody of Waka murasaki. In his view, inversion (hanten) is the “method” of parody in Mushi mezuru. Based on statements that Waka murasaki is alluding to Ise monogatari,43 Higashihara claims that Mushi mezuru is a double parody as the links reach both Genji and Ise (besides Ise through Genji). Inversion (hanten) of classical patterns of kaimami creates parody, Higashihara states.44

As I have argued above, parody in late Heian–Kamakura court fiction seems to have an episodic nature, adapting the form of setsuwa. We have no examples of full-scale parodic monogatari, but only short episodes and amusing subplots that can be recognized as a part of lengthy monogatari. Some short stories (tanpen monogatari) of Tsutsumi makes an exception here and in these stories humor and parody are crucial elements to the extent that one is unable to interpret them if one is not able to decode these parodic elements.

The story ends with the narrator’s comment pointing out that “it must be (written) in scroll two” (ni no maki ni aru beshi), thus inviting the reader to imagine how the story continues ‒ the open question is whether the Assistant Director of Stables of the Right (Uma no suke) able to cultivate the caterpillar lady, in the same way as Hikaru Genji brought up Murasaki no Ue.

The phrase preceding this open ending states that “(he) laughed and seems to have returned home” (warahite kaerinu meri). The particle meri marks a supposition, guess or hypothesis (it seems, it appears that). Among the several other particles that have the same kind of function, the specialty of meri is that it contains a visual dimension, a connection to the concrete act of seeing. Thus the narrator, who seems to be watching the situation, wonders if Uma no suke really returned or not. In other words, this open ending suggests that the story continues. Maybe the hero has not really gone but is hidden somewhere nearby and is coming back? Maybe the story of the two is still continuing?

In conclusion, humorous and parodic elements seem to have a crucial role in the text in question. The mockery seems to be targeted towards court society, but the critical shades are light as the author her/himself must have belonged to the same social circle. The interpretation of this short story as some sort of game or quiz, where the author is stimulating her/his reader’s imagination, casts new light on humorous short stories.

However, it is important to note that the parodic aspects of this story are just one possible reading of it: there are also references to Buddhist and Taoist works, and these discourses may have been intended to be read rather seriously. In addition to the parodic interpretation, there are two common readings that have been suggested: one that highlights its Buddhist aspects and one that interprets the story as an allegory of sexual maturing.45 However, in this paper I shall limit the focus on the parodic elements.

Even prettier than a lady

The same thematic elements can be found in the medieval monogatari known as Kaze ni momiji『風に紅葉』, where the protagonist Taishō is deeply moved at finding a little boy, who is “even prettier than a woman” (onna no sama yori mo wokashige nari). Like Hikaru Genji, he discovers a lovely child whose innocence and cuteness fascinate him.

The reader soon becomes conscious of the clear similarities with the Waka Murasaki chapter of Genji. Taishō is yearning for the Imperial Consort, who actually is his aunt, just like Hikaru Genji has adored his stepmother Fujitsubo since childhood. One should note here as well that the allusion to Genji is partially created by similarities in the relationship between the characters.

One clear similarity between Genji and Kaze ni momiji is that 18-year-old Hikaru Genji, is separated from his usual life in order to receive prayers and incantations (kaji) from a Buddhist esoteric (hijiri) in Kitayama; and in the same way Taishō goes to meet a Buddhist esoteric, and finds the young boy (Waka gimi). The description of the child’s appearance clearly resembles that of young Murasaki:

・・・限りなううつくしげなる女のささやかなるぞゐたる。いとおぼえなくて、近く寄りて見給へば、十一、二ばかりなる人の白き衣に袴長やかに着て、髪の裾は扇を広げたらんやうにをかしげにて、かたちもここはとおぼゆるところなく、一つづつうつくしなどもなのめならず。さるは、わが御鏡の影、女御などにぞおぼえきこえたる。(三五頁)

『風に紅葉・むぐら 』「風に紅葉」46

… (Taishō saw that) there was an extremely beautiful little girl. It was completely unexpected to him, so he approached her to watch closer. There was an about 11- or 12-year- old person, wearing a white gown with a very long hakama skirt, and the tips of her/his hair cascaded beautifully like a spread fan behind her/him. Her/his features were without the slightest fault and beautiful, nothing particularly standing out. On top of that, he/she resembled his own reflection in the mirror, as well as that of Senyōden Consort.47

While Genji immediately recognizes the resemblance to Fujitsubo, Taishō notices that Waka gimi looks just like his own reflection in the mirror, or that of his sister Senyōden Consort. In fact, the father of Taishō and his sister, Kanpaku sadaijin, is also the grandfather of Waka gimi (by a different mother). Therefore, they are related to each other.

The allusion is further stressed when Taishō is then said to carry the child to the wagon “like a woman” (kono gimi woba onna no yau ni hikisobamete, nosekikoe tamafu) and to steal the child like Hikaru Genji stole Murasaki.

出で給ふにも、この君をば女のやうにひきそばめて、乗せきこえ給ふ。ほどなく綱手はやく曳かせて、夕つ方、都に着き給ひぬ。(三八頁)

『風に紅葉・むぐら 』「風に紅葉」48

When he left, he took Waka gimi (the young boy) and lifted him into the wagon next to him like a lady. Soon (they changed to a boat and) he had the mooring rope taken in. In the evening they reached the capital.

In contrast to Hikaru Genji, Taishō does not intend to hide his new favourite from his wife, but instead brings the child with him to his residence. He presents Waka gimi to his wife, asking “Are you worried that (she) is a woman?” Against all expectations, his wife turns out to be delighted to find that the child is a boy.49

Taishō instructs an attendant called Ben to serve as a nurse (menoto) for the child and to sleep with him, but Waka gimi protests with lowered eyes by saying “If I can’t be by your side, I want to sleep alone.”50 Taishō agrees to sleep with him, and thus the three, Waka gimi, Taishō and his wife Ippon no miya sleep together side by side. Here the narrator skeptically comments on the scene “(I) wonder how this is going to end, there is a tendency to recklessness in this text.” Later on, the description clearly shows that Taishō and Waka gimi are having a sexual relationship.

弁といふ人を御乳母につけて、「夜もそれと寝給へよ」とおほせらるれば、伏し目になりて、「御そばならずは、ただ一人寝ん」とのたまふ心苦しさに、また、「さらば、いざ」とて、宮の御そばへも具しきこえ給ふ。 (三九頁)

ついのはいかがあらん。例のさざしかるらん、この冊子の。(四〇頁)

『風に紅葉・むぐら 』「風に紅葉」51

He attached an attendant called Ben to serve the boy as a nurse, and instructed her to sleep with him. But with lowered eyes the boy said: “If I can’t be by your side, I want to sleep alone”, so heartbreakingly that Taishō assumed “Well, alright then”. So the boy followed Taishō next to Ippon no miya (Taishō’s wife).

I wonder how this is going to end, there is a tendency to recklessness in this text.

Here the narrator skeptically comments on the scene “(I) wonder how this is going to end, there is a tendency to recklessness in this text.” Later on, the description clearly shows that Taishō and Waka gimi are having a sexual relationship.

Disturbed love

The story of Kaze ni Momiji forms an interesting counterpart to another medieval monogatari, Koiji yukashiki taishō, which also contains a distorted version of Waka Murasaki. While Hikaru Genji becomes interested in 10-year-old Murasaki, Genji and Murasaki getting married (niimakura) four years later (as a girl was considered adult after her mogi ceremony usually around the age of 14), in Koiji the protagonist “Koiji”52 is 27 years old when his relationship with the 12-year-old Second Princess begins.

As some scholars, such as Karashima Masao and Ogi Takashi,53 have pointed out, there is an apparent parallelism between the relationship of the characters in Koiji and Genji. For example, Koiji is attached to the Second Princess (Onna ni no Miya), who represents Tama Hikaru (Fujitsubo Consort). This is similar to Genji’s fixation on Fujitsubo, whose substitute (yukari) is Murasaki. Thus the relationship of the characters forms the following parallelism:

Genji: Hikaru Genji — Fujitsubo — Murasaki

Koiji: Koiji — Tama Hikaru — Second Princess (Onna Ni no Miya)

In my view, there are clearly many allusions that connect Koiji’s story to the Waka Murasaki chapter. Onna Ni no Miya is even called Wakakusa, in a phrase that alludes to poems that appear in Waka Murasaki, for instance:

世をわがままにのみ思さるる心おごりには御ざあがりなどは、まいて何とかは御心にも染まん、ただ若草のねみん事のみ心もとなきに、またさしも忍びし恋のあらはれにしも、かたがた御心の忍ぶもぢずり乱れまさり給ふがあぢきなき紛らはしには… (六六頁)

『恋路ゆかしき大将、山路の露』「恋路ゆかしき大将」54

As he was just waiting for things to turn out according to his own will, how did he find his own condition (about his own rise in rank)? He could not help thinking of nothing else but sleeping with the young Princess, Waka kusa (Onna Ni no Miya, Second Princess), and what if his hidden love were revealed. On the other hand, his hidden feelings became more and more disturbed and shameful … 55

(尼君)「おひ立たむありかも知らぬ若草をおくらす露ぞ消えむ空なき」(一五七頁)

『源氏物語』「若紫」56

”When no one can say where it is, the little plant will grow up at last, the dewdrop soon to leave her does not see how she can go,” the nun said (p. 87).57)

Further on, the marriage, or niimakura of Koiji and Onna Ni no Miya evokes the niimakura of Genji and Murasaki:

いかなる朝にかありけん、男の御有様もつれなし作りあへず、女宮も起き給はで、暮れゆくを悩ましくおはしますにこそは。されど院にかくとは聞こえさせじと深くもて隠し給ふにぞ、中納言の君などは心得ける。(七四頁)

『恋路ゆかしき大将、山路の露』「恋路ゆかしき大将」58

Then one morning, the man could not pretend to be indifferent, and the Princess did not rise at all, feeling unwell for the entire day. However, she did not want to let The Retired Emperor know about her secret and was hiding it carefully, while Chūnagon and the others guessed what had happened.

いかがありけむ、人にげぢめ見たてまつり分くべき御仲にもあらぬに、男君はとく起き給ひて、女君はさらに起きたまはぬあしたなり。(一二六頁)

『源氏物語 』「末摘花」59

… it came to pass one morning, when there was nothing otherwise about their ways with each other to betray the change, that he rose early while she rose not at all (p. 186).60)

On the other hand, Sukegawa Kōichirō,61 among others, has argued that many conventional patterns of monogatari have been broken in this tale (物語破壊).62) As Sukegawa points out, the author seems to be consciously “borrowing the composition of a ‘monogatari like tale’ (monogatari-rashii monogatari) and then changing it into a ‘non-monogatari like’ tale”.63 In my view, in some cases we can find what Hutcheon would call “ironic ’trans-contextualization’ and inversion, repetition with difference”.

As Karashima Masao has pointed out, the protagonist is 9 years older than Hikaru Genji, and hence the “monogatari-like romanticism” (monogatari-rashii romanchishizumu) is completely annihilated by his monomaniacal (henshitsukyōteki) attachment. Koiji attentively plays with hina-dolls with the young lady, echoing the way in which young Genji played with Murasaki. However, the image of an almost 30-year-old adult man being occupied with a 12-year-old girl on the miniature capital leaves a rather comic or even grotesque impression. Indeed, Koiji himself seems to be rather puzzled by the situation, and the narrator regards his behaviour as foolish:

わが御心ちにも、そぞろなる事かなとをかし。

我ながら言ふかひなやと思ふかな野なる虫にも宿をしめさす かつはをこがましう、かかるいたづら事のしおかるるも、上の空なる心化粧なり。(五四頁)

Koiji himself found his mind reckless and strange:

Even for me, I found it foolish, giving to wild insects a lodging, while doing that kind of stupid thing occurred just because I would like to please the Second Princess.

It has been argued that this tale reflects the reality of the court society of that time, reflecting its degeneration since the glorious heyday during the Heian period. In my view, this kind of “realism” breaks the illusion of monogatari, the fictive and idealized world, thus creating “repetition with difference” and “ironic inversion”.64

Conclusion

In the previous examples, I have illustrated how the famous story of Murasaki no Ue was alluded to and rewritten in later monogatari tales. The nature of parody seems to be episodic and rather following the conventions of writing than breaking them.

In addition to these allusions, it must be remembered that allusions to the story of Murasaki can be found in a number of other works of court fiction, such as Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari and Yowa no nezame. Apparently the well-known story of Murasaki was read as a kind of Cinderella story of a young girl discovered by the ideal prince.

In medieval monogatari, the theme of the fortunes of women (onna no kōfuku no monogatari), leading to a “happy ending”, seems to have been a common pattern. Hence, parodic reformulations of the story of Murasaki can sometimes be seen as ironically commenting on this convention as well: while Murasaki becomes Genji’s most adored woman, in all my examples the reader’s expectations are ultimately betrayed, since the outcome of these encounters is always something else.

Finally, as all my examples show, the parody of medieval monogatari can be described as “repetition with critical distance”, as Hutcheon would put it. Hutcheon’s concept, can provide a practical tool to analyze allusions that cannot be grasped otherwise.

As stated before, the so-called realism of these tales creates critical distance with the idealized monogatari world, when the illusion is broken. If I were to sum up some tendencies common to all the examples, one could be the reversal of the reader’s assumptions, since in all cases the monogatari-like frame is first created and then subverted ‒ in a manner that could indeed be described as “ironic inversion” as Hutcheon would use the term.

References 参考資料

伊井春樹 「中世における源氏物語享受史の構築」『中世文学』、 第四十五号、中世文学会、 東京、2000年

伊井春樹『源氏物語を学ぶ人のために』世界思想社、東京、1993年

市古 貞次『日本古典文学大辞典』第6巻 【も‐を索引】岩波書店、東京、1985年

岩佐美代子 「伏見院宮廷の源氏物語-鎌倉末期の享受の様相」『源氏物語とその前後 研究と資料』 紫式部学会、 武蔵野書院、東京1997年

小木喬 『鎌倉時代物語の研究』東京書房、東京1961年

大倉比呂『 志物語文学集攷―― 平安後期から中世へ ―― 』(新典社研究叢書236) 新典社、東京2013年

大槻修 神野藤昭夫『中世王朝物語を学ぶ人のために』世界思想社、東京1997年

辛島正雄『中世王朝物語史論 上巻』笠間書院、東京2001年

辛島正雄「中世物語史私注 ― 『いはでしのぶ』『恋路地ゆかしき大将』『風に紅葉』をめぐって」徳島大学教養部紀要 (人文・社会科学) 第21巻、1986年3月

木村朗子「権力再生産システムとしての〈性〉の配置 『とりかへばや物語』から『夜の寝覚め』へ」物語研究 第2号、2002年

島内景二 「『恋路ゆかしき大将』の話型論的研究」『電気通信大学 文学研究室報告書 I』 電気通信大学・文学研究室、1992年

下鳥朝代「「虫めづる姫君」と『源氏物語』北山の垣間見」『国語国文研究 (北海道大学国語国文学会)』第94号、1993年7月

助川 幸逸郎 「『恋路ゆかしき大将』における<物語破壊> : <女性嫌悪>と<『法』としての父権>」 物語研究 (6)、2006年

高田 祐彦『古今和歌集』 角川学芸出版、東京2009年

立石和弘「虫めづる姫君論序説—性と身体をめぐる表現から—」In 『堤中納言物語の視界』王朝物語研究会、東京 1998年

玉上琢弥(訳・注) 『源氏物語 』第一巻 桐壺~若紫 角川学芸出版、東京1964年

玉上琢弥(訳・注)『源氏物語 』第二巻 末摘花~花散里 角川学芸出版、東京1964年

ツベタナ・クリステワ『パロディの理論と日本文学』Asian Cultural Studies Special Issue No. 16・アジア文化研究別冊 16 「パロデイと日本文化」2007年International Christian University Publications, 2007年

中西 健治 常磐井 和子 (訳)『風に紅葉・むぐら 』(中世王朝物語全集) 、笠間書院、東京2001年

西本寮子 「『源氏物語』と院政期物語」『講座 源氏物語研究 第四巻 鎌倉・室町時代の源氏物語』おうふう、東京2007年

西本寮子「『とりかへばや』と『源氏物語』―匂宮三帖への関心を視点として―」 森一郎『源氏物語の展望 第八輯』三弥井書店、東京2010年

三角洋一(訳・注) 『堤中納言物語』 講談社 、東京1981 年

三谷邦明 「擬く堤中納言物語—平安後期短編物語の言説の方法あるいは虫めづる姫君物語を読む—」石川徹『平安時代の作家と作品』武蔵野書院、東京1992年

三田村雅子『記憶の中の源氏物語』新潮社、東京2008年

三田村雅子 『天皇になれなかった皇子のものがたり』 新潮社、東京2008年

稲賀 敬二 (訳)『恋路ゆかしき大将、山路の露』(中世王朝物語全集) 笠間書院、東京2004年

塙 保己一『弘安源氏論議』『群書類従』第十七輯 連歌部・物語部 池田亀鑑編『源氏物語事典 下』中央公論社、東京1960年

東原伸明「虫めづる姫君」のパロディ・ジェンダー・セクシャリティ」IN 物語研究会『新物語研究 3 物語<女と男>』有精堂、東京1995年

福田秀一 「中世文学における源氏物語の影響」、34項 『中世文学論考』第一編 第一章、明治書院、 東京1975年

Backus, Robert L. (transl.). The Riverside Counselor’s Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1989.

Dentith, Simon. Parody. Routledge, Oxon 2000.

D’Etcheverry, Charo B. Love After The Tale of Genji: Rewriting the World of the Shining Prince. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2007.

Hutcheon, Linda. A theory of parody: the teachings of twentieth-century art forms. University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago 2000 (1985).

Miner, Earl & Odagiri Hiroko & Morrel, Robert E. The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1988.

Morris, Ivan . The World of the Shining Prince. Court Life in Ancient Japan. Oxford University Press, London 1964. Okada, H. Richard. Figures of Resistance: Language, Poetry and Narrating in The Tale of Genji and Other Mid-Heian Texts. Duke University Press, Durham and London 1991.

Rodd, Laurel Rasplica & Henkenius, Mary Catherine (transl.). Kokinshu: A Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern. Cheng & Tsui, Boston, Massachusetts 1996.

Rose, Margaret. Parody: ancient, modern, and post-modern. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993.

Rose, Margaret. Parody//meta-fiction: An Analysis of Parody as a Critical Mirror to the Writing and Reception of Fiction. Croom Helm, London 1979.

Tyler, Royall (transl.). The Tale of Genji. Penguin Books, New York 2003.

- The term monogatari 物語 generally refers to tales or prose narratives of various kinds. Monogatari has two meanings: to relate (kataru) things (mono), and a person (mono) who relates (kataru) (See for instance Miner et al. 1988, 290). In this paper, monogatari primarily refers to chūsei ōchō monogatari 中世王朝物語medieval court fiction, i.e., monogatari that are estimated to be written during late Heian‒Kamakura period (See Ōtsuki et al. 1997, 4‒8, 29‒33). [↩]

- See, for instance, Mitamura 2008. [↩]

- Nise murasaki inaka Genji, written by Ryūtei Tanehiko, is a late Edo-period parody of Genji monogatari. It was published between 1829 and 1842. This and many other literary parodies were produced during Edo period, due to remarkable changes in cultural climate and publishing industry. The beginning of 17th century saw appearance of huge amount of popular parodic literary, including whole new genres. [↩]

- See Kristeva 2007, 6‒7. [↩]

- Mitani 1992, 68. [↩]

- See Hutcheon 2000, 32. [↩]

- Hutcheon 2000, 32. [↩]

- Ibid., 31 [↩]

- According to Rose, Hutcheon has misrepresented the role of humor in parody. In Rose’s view, Hutcheon’s statement that “in classical uses of the word parody, humor and ridicule were not considered part of its meaning” is misleading. According to Rose, Hutcheon’s effort to separate parody from the comic makes her theory a “late-modern” reaction rather than “post-modern” since it reduces the “modern” description of parody as burlesque comedy. (Rose 1993, 239 [↩]

- 「塙 保己一『弘安源氏論議』『群書類従』第十七輯 連歌部・物語部 池田亀鑑編『源氏物語事典 下』中央公論社、1960年 [↩]

- My own translation. [↩]

- 高田 祐彦『古今和歌集』 角川学芸出版、2009年 [↩]

- Kokinshu: A Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern. (Translated by Laurel Rasplica Rodd & Mary Catherine Henkenius. Boston, Massachusetts: Cheng & Tsui, 1996). [↩]

- Nishimoto 2007. [↩]

- Hutcheon 2000, 6. [↩]

- D’Etcheverry 2007, 16, 21. [↩]

- Fukuda, 1975. [↩]

- 玉上琢弥(訳・注) 『源氏物語 』第一巻 桐壺~若紫 角川学芸出版、1964年 [↩]

- The Tale of Genji. (Translated by Royall Tyler. Penguin Books, 2003). [↩]

- Warawa yami may refer to malaria, but it has been suggested that the word could also be understood as “childhood (warawa) illness (yami)”, that is “inflicted with an ailment as (or from the time of) a child.” See, for instance, H. Richard Okada, “Substitutions and incidental narrating ‘Wakamurasaki’” in H. Richard Okada, Figures of Resistance: Language, Poetry and Narrating in The Tale of Genji and Other Mid-Heian Texts (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1991). [↩]

- H. Richard Okada, “Substitutions and incidental narrating ‘Wakamurasaki’”. [↩]

- In the case of the first Chapter of Ise monogatari (Tales of Ise), 1) the young protagonist “the man of ancient times” (mukashi otoko) 2) has attained adulthood (the ceremony of uikōburi), and as he goes 3) to the village of Kasuga (kasuga no sato, present Nara) 4) to hunt, he 5) accidentally catches a glimpse (kaimami) of two (or only one, based on another possible reading) fascinating girls, is profoundly confused and writes a poem for the girls. In the case of Genji, 1) the young protagonist Hikaru Genji 2) has fallen ill (warawa yami), and he goes 3) to Higashiyama (north of Kyoto) 4) for incantation (kaji) and 5) accidentally discovers a young girl. Based on “inversions” from 1) to 5) it has been argued that Wakamurasaki is referring to Ise. See, for instance, Shimatori 1993. [↩]

- p. 40. [↩]

- p. 54 [↩]

- 荒らかに踏みて出づ [↩]

- p. 52 [↩]

- 三角 洋一 (訳・注) 『堤中納言物語』 講談社 、1981 年 [↩]

- The Riverside Counselor’s Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan

(Translated by Robert L. Backus; Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989). [↩] - Mitani 1976. [↩]

- Shimatori 1993. [↩]

- A search of the database Japan knowledge (both hiragana and kanji ) shows, apart from Waka murasaki (three hits) one hit in Genji’s chapter Suetsumu hana and one hit in Kashiwaki. In other works, there were only four hits in total (in Izayo nikki, Sasekishū, Taiheiki and Ukiyoe monogatari). [↩]

- 『源氏物語 』第二巻 末摘花~花散里、角川学芸出版、一九六四年 [↩]

- 『源氏物語』第一巻 桐壺~若紫、角川学芸出版、一九六四年 [↩]

- The Tale of Genji. (Translated by Royall Tyler. Penguin Books, 2003. [↩]

- 三角 洋一 (訳・注) 『堤中納言物語』 講談社 、1981 年 [↩]

- 三角 洋一 (訳・注) 『堤中納言物語』 講談社 、1981 年 [↩]

- The Riverside Counselor’s Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan. (Translated by Robert L. Backus; Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989). [↩]

- The word mushi 虫 may refer to all kind of insects, frogs and even birds and other small animals. [↩]

- About the beauty concepts of late Heian court, see for instance: Morris 1964. [↩]

- The kaimami scene is actually preceded by an episode where Uma no suke sends the lady a snake that he has made himself. As has been pointed out (see, for instance, Higashihara 1995), the snake is closely associated with the male sex. The story can also be read as a humorous description of sexual maturing: one day this rebellious teenager will inevitably grow into a woman, just like caterpillars that metamorphose into butterflies. [↩]

- Ii 1993. [↩]

- Shimatori 1993; Ii 1993. [↩]

- See, for instance Shimatori 1993. [↩]

- Higashihara 1995, 202–203. [↩]

- See, for instance, Tateichi 1998. [↩]

- 中西 健治 常磐井 和子 (訳)『風に紅葉・むぐら 』(中世王朝物語全集) 、笠間書院、2001年 [↩]

- All translations for Kaze ni momiji are my own. [↩]

- 中西 健治 常磐井 和子 (訳)『風に紅葉・むぐら 』(中世王朝物語全集) 、笠間書院、2001年 [↩]

- “I got a daughter” (娘をまうけて侍り), Taishō remarks to his sister. [↩]

- 「御そばならずは、ただ一人寝ん」 [↩]

- 中西 健治 常磐井 和子 (訳)『風に紅葉・むぐら 』(中世王朝物語全集) 、笠間書院、2001年 [↩]

- As the title of the protagonist is constantly changing according to his promotions, he has generally been called Koiji by researchers for the sake of convenience. [↩]

- See Ogi 1961, 172-173. [↩]

- 宮田 光 稲賀 敬二 (訳)『恋路ゆかしき大将、山路の露』(中世王朝物語全集) 笠間書院、2004年 [↩]

- All translations of Koiji yukashiki taishō are my own. [↩]

- 玉上琢弥(訳・注) 『源氏物語 』第一巻 桐壺~若紫 角川学芸出版、1964年 [↩]

- The Tale of Genji. (Translated by Royall Tyler. Penguin Books, 2003. [↩]

- 宮田 光 稲賀 敬二 (訳)『恋路ゆかしき大将、山路の露』(中世王朝物語全集) 笠間書院、2004年 [↩]

- 玉上琢弥(訳・注)『源氏物語 』第二巻 末摘花~花散里 角川学芸出版、1964年 [↩]

- The Tale of Genji. (Translated by Royall Tyler. Penguin Books, 2003. [↩]

- See Sukegawa 2006, 145‒158. [↩]

- For instance, there are three characters who could be the protagonist. The acts of the brothers, Hayama no Shigeri(端山の繁り) and Hanazome (花染), are the subject of most of the story, while Koiji mostly acts only in the first two chapters. However, his appearance is described as more appealing than the two brothers, and he seems to have a special “lustre” (光) that usually is attached to the protagonist. (See Sukegawa 145‒147. [↩]

- 「物語らしい物語」の構図を借りてきて、「物語らしくない物語」に改変する [↩]

- Despite implicit allusions to Murasaki’s story, the focus shifts later to another relationship in Genji, that of Hikaru Genji and his step-daughter Tamakazura, as Koiji finds Ippon no Miya looking at a picture that shows Tamakazura and Genji, thus creating an interesting scene that resembles the technique called mise-en-abyme. [↩]