Filosofian maisteri Riikka-Maria Pöllän historian alan väitöskirja ”Refashioning the Respectable Elite Woman in Louis XIV’s Paris — Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos” tarkastettiin 28.4.2017 Helsingin yliopistossa. Vastaväittäjänä oli professori Yme Kuiper (Groningenin yliopisto, Alankomaat) ja kustoksena professori Laura Kolbe. Väitöskirja on luettavissa osoitteessa: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-3043-3.

“Si la science & la sagesse se trouvent unies en un même sujet, je ne m’informe plus du sexe, j’admire”. In other words, the 17th century French philosopher Jean de La Bruyère defined educated women as follows: if knowledge and wisdom meet in a single person, I no longer ask what sex they are, I admire.

My study analyses two educated and admired elite women: Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos. Furthermore, the study is about their self-fashioning, about their success in their performances among Parisian elite society and about the dichotomy between the reality and ideals. I refashioned the requirements of status for the respectable woman: in other words, l’honneste femme.

The leading ladies of my study: the respectable marquise de Sévigné and courtesan de Lenclos had to find balance between their own ambitions and the early modern French society that highlighted the superiority of their male peers. Not to mention the stricter rules placed on sexuality and importance of female chastity in understanding respectable woman, which has been highlighted in 17th century conduct books and previous studies. However, my study argues that respectable French women did not have to follow absolute chastity to gain the title of the epoch’s female ideal, l’honneste femme. But how could I make such a statement?

As all historians know, it is all about sources. The source material suggested that female chastity is not the only key factor when evaluating l’honneste femme. Indeed, according to documents it seemed that l’honneste femme of the Parisian elite was composed from different elements: elite status meaning family background, education, manners, material culture, outer appearance and sexuality; residential area also played a role, especially the quartier of Le Marais with its flourishing elite culture.

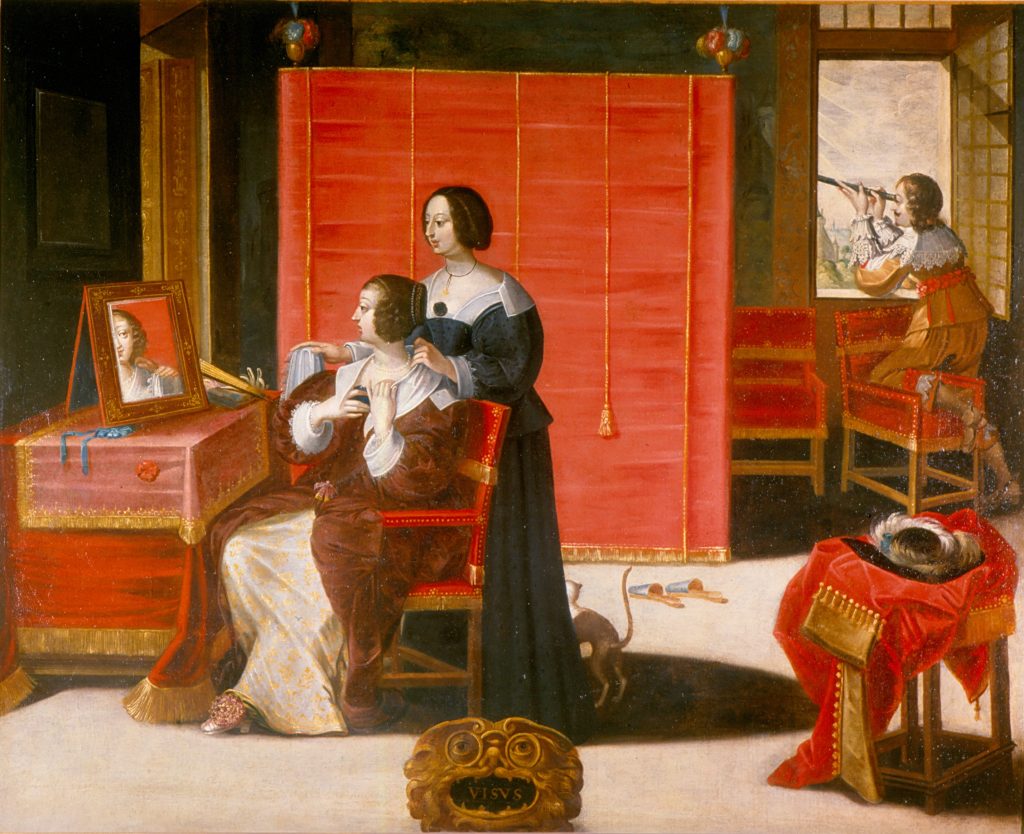

In the 17th century a person’s outer appearance reflected his or her inner beauty. It was not only a question of polished manners of Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos, or their detailed performance among their peers: the visual signs such as clothing and carefully created outer appearance were also significant. In this context, a visual vista may be worth a thousand PhD dissertations. This said, let’s have a closer look at the paintings of Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos. What can they tell us about the elite women who lived morally so different lives but in the end, they both enjoyed the status of a respectable woman?

In spring 2015 I was teaching Baroque Women at the University of Helsinki with my dear colleague Doctor Rose-Marie Peake. One day I showed these two paintings in which we can see two perfectly polished elite women during their best years, wearing fashionable clothes made of damask or taffeta, not to mention precious stones, pearl jewellery and curled hair. Our students had to figure out which one was the marquise and which one the courtesan. The students’ explanations varied, and this did not surprise us. As you might guess by now, the question is complex and therefore, we had a fruitful discussion about the images of these women and how it would be possible to separate the chaste and respectable marquise from the blooming and sexually active courtesan. And I think here is one of the key notions: comparing Madame de Sévigné’s and Ninon de Lenclos’ appearances, it is impossible to say for sure who is a chaste widow and who is enjoying a sexually liberated lifestyle. Indeed, these two 17th-century elite women looked alike and their outer appearances were a feast for the eyes even though their understanding of acceptable female sexuality differed.

In this context, the need to dig deeper into Parisian elite women’s lives was highlighted in order to better understand what the actual essence of l’honneste femme was. After putting considerable effort into understanding the 17th century human ideal and comparing la marquise and la courtisane, the demand of absolute chastity for a respectable woman turned out to be too simple an explanation. Thus, the dichotomy between ideals and reality became self-evident.

Of course, no one can deny that Parisian vices appeared and condensed in the life of courtesan de Lenclos, and in her close circle. Ninon de Lenclos was not conventional, her mother decided to procure her, her passionate father was exiled and Ninon herself never got married. Thus, she did not receive support from family, but neither did she have relationships that restrained her. However, she was an educated, sophisticated woman who could — with the support of her noble and elite friends — clear her way to the top of Parisian elite, and to achieve an unquestionable place in it. In her youth, her sexual choices led her to lose the most highlighted feature of female respectability, sexual purity, but she was still able to compensate this with other attributes of the respectable woman discussed earlier, such as elite lifestyle, education and polite manners. Madame de Sévigné, the daughter of a baron and a wealthy mother, appears as a respectable and sophisticated member of the elite all her life. She was conscious of her choices and her status as a wife and as a widow. Furthermore, she also performed as a loving mother. In other words, whereas Madame de Sévigné negotiated successfully with the demands of the society of her epoch, Ninon de Lenclos, in her turn, did not only critique, I claim, the social order, but she also participated in that order as an independent woman. Indeed, she was able to act and use her mise en scène as a stage for her spectacle and self-fashioning as one of the honnêtes gens. She made herself different and unusual. Indeed, Ninon de Lenclos made herself into a brand, one that was interesting and desirable.

Women’s continual obedience to rules and duties, the performance of politeness in elite meetings, and attention they received from their peers meant that a respectable woman was constructed above all in a public space. Thus, elite women had to be careful when making choices in their self-fashioning: the hierarchies, interpersonal discourse, and women’s own choices determined how their status among the elite was formed. Furthermore, l’honneste femme was constructed through mental images, which people formed when they processed all possible information and messages.

Indeed, elite living, not to mention female sexuality and its manifestation created mental pictures, which came together with an enormous amount of moral values, ideas of manhood and womanhood, and established expectations for the female gender: however, the female ideal of the elite was not iron-cast, and through the right kind of self-fashioning and honnête lifestyle choices, an elite woman could strengthen her position and even climb the social ladder. Yet, I suggest that achieving of the ideal required that each and every criterion were met. Even though Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos were mighty opposites in terms of their sexual behaviour, they both fashioned their status through the elite lifestyle and achieved the status of respectable woman. Of course, Madame de Sévigné managed to fashion herself as l’honneste femme throughout her life, whereas Mademoiselle de Lenclos only achieved the status at an older age. Despite this, both Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos made themselves respectable legends through their careful self-fashioning. Thus, the status of a respectable woman was not impossible to achieve if an otherwise cultivated elite woman renounced her immoral behaviour and continued to fashion an honnête lifestyle.

Thus, by comparing Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos, the study points out that following the detailed elite lifestyle, an educated woman from a noble family could gain the status of respectable woman as long as she one day abandoned her sexually open lifestyle. Most importantly my study shows that the external signs of l’honneste femme played a greater role than previous scholars have assumed. In other words, a respectable woman’s honnête performance was created from many different social and personal aspects, of which chastity was only one of them. Indeed, 17th-century Parisian elite women had to be able to uphold simultaneously different status layers of their rank to fulfil the expectations that the Ancien Régime created for l’honneste femme. In addition, my PhD theses suggests that the respectable Parisian elite woman could make her own decisions in relation to her lifestyle and self-fashioning and these actions were essential when constructing the entity of l’honneste femme.

To conclude, I would like to highlight that I am convinced that the issues discussed in the study hold significance also for the present, for us: the study concerns subjects, which are still relevant today, such as the female ideal, virtue and sexuality. Women’s self-fashioning among their societal circles is also always important. Thus, it is reasonable to ask if people’s need for societal performances has really changed much? My study revealed not only how the women of the early modern era form a continuum that extends to present day women. In my study, this problem has been approached from the perspective of the layered nature of honneste femme, its fashioning and a central voice was given to two women of 17th century Parisian elite. The stories of Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos have been excellent examples of a broader European development and attributes which have been linked to womanhood, and which are still defining how women are perceived, and what their reputation and role in the current society are like. For this reason, the lives of Madame de Sévigné and Ninon de Lenclos are, I believe, justified to be discussed also at the University of Helsinki.