FM Lasse Lehtosen musiikkitieteen / Aasian tutkimuksen väitöskirja ”’March from the Age of Imitation to the Age of Creation’: Musical Representations of Japan in the Work and Thought of Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei, 1930-1940” tarkastettiin 20.4.2018 Helsingin yliopistossa. Vastaväittäjänä toimi emeritaprofessori Bonnie Wade (University of California, Berkeley) ja kustoksena professori Kai Lassfolk (Helsingin yliopisto). Väitöskirja on luettavissa verkossa: http://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/233760

The decade preceding World War II in Japan was characterized by stark internal divisions, contradictions, and conflicts like no other. In many ways, they stemmed from what was perceived as the conflict of Japanese tradition and Western modernity. Japan had been adopting Western culture and technology for over 60 years, and become an international and modern society on Western standards. This came at a cost, however: the most avid years of modernization had largely neglected Japanese culture, which is why the very same period saw the first large counter-reaction to this. It emerged as the revaluation of traditional Japanese culture, but simultaneously contributed to the rise of an aggressive form of nationalism, eventually with tragic consequences.

Of course, this we all know too well. Today, the years before the war are all too easy to recognize as a path naturally leading to conflict. In reality, the situation was more complex than this: while the revaluation of Japanese culture in the 1920s and 1930s did eventually surface as aggressive opposition of the West, it also appeared as nostalgic longing for an idealized past, for example. These aspects emerged in the same social context, but they were fundamentally different from each other.

These are also some of the reasons why Japan of the 1920s and 1930s has been researched from various points of view that seek to shed light on what was happening in Japanese society of the time. This ranges from economy and politics to various fields of culture and the arts. In this context, it is interesting that several fields of arts saw the emergence of movements that synthesized aspects of Western modernity and Japanese tradition during this period. Music is no exception. Previous research has noted that the contradictions of the society were apparent in commercial popular music as well as in the innovations made in the field of traditional music. In Western art music composition by Japanese composers, however, much still remains unknown. To be more precise, the history of composition in Japan has been largely fixed on the idea that it was truly born only in the postwar period with internationally successful composers such as Tōru Takemitsu (1930—1996).

These issues are the starting point of my research. In my doctoral dissertation, I wanted to examine music and composers against the complex situation in prewar Japan, and also critically re-inspect the history of Western art music composition in Japan. More precisely, my research focuses on the study of what I call — and composers of the time called —”Japanese-style composition”. In my dissertation, it refers to music that is based on Western principles of composition, such as Western instrumentation and Western notation, but utilizes elements from Japanese culture in the expression, such as scales and forms of traditional music, and traditional concepts of aesthetics. ”Traditional” refers here to forms of culture that existed in Japan before the active adoption of Western culture launched in 1868, but does not suggest a uniform or unchanging culture.

Why is it important to study Japanese-style composition in the context of the 1930s? Of course, the first apparent reason is that influences from Japanese culture in the work of Japanese composers has been fascinating scholars both in Japan and the West, and also my study is about understanding what Japanese-style composition actually was on a musical level. It was also a new and heatedly debated topic among composers of the time, which underlines its significance in the 1930s. In this sense, my research is a contribution to understanding what the concept of ”Japanese” meant in musical terms.

In the context of the 1930s, however, the approach of analyzing these qualities goes beyond simple analysis of musical expression: to me, it seems that this compositional style reflects the very contradictions and complexities of Japan of the time. It is rooted in both Western and Japanese traditions, and thus possibly suggests cultural synthesis — but conflicts as well, as it could be seen as the antithesis of Western-style composition. In this way, Japanese-style composition offers one viewpoint to how music possibly reflected and created tendencies in the society.

Of composers of the time, my research focuses on the sixteen founding members of a composer society called Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei. Through the analysis of the musical work and thought — or writings and interviews — of the composers, I wanted to find out what Japanese-style composition of the 1930s was: what it was musically, how it emerged, and how it related to the social developments of the time. In this context, I consider musical works as objects of art that communicate and construct culture of their time. For this reason, I also want to emphasize the role of the writings of composers in trying to figure out what Japanese-style composition represented for each of them; simply analyzing musical works seemed an inadequate approach when trying to grasp also cultural contexts.

The most important reason to choose this approach — that can admittedly be called both composer and work centric, and thus representing ”traditional musicology” — is that musical works of the time have still been rather scarcely analyzed. I wanted to view them from the premises of the composers, who, after all, identified with the tradition of Western art music composition, albeit as Japanese and Japanese-style composers.

Numerous previous studies have acknowledged Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei as the forerunner of Japanese-style composition of the time. It was founded in 1930 to promote modern styles of music and to oppose the simple mimicking of Western composers, which is also expressed in its early slogan: ”March from the age of imitation to the age of creation.” Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei later grew to be the largest composer group in Japan, and it was also a very international society, as it later became the Japanese branch of the International Society for Contemporary Music, and many of the composer’s works were performed in Europe. As such, it is also the predecessor of the current Japan Society for Contemporary Music. However, it was forced to disband in 1940 by a governmental order, which encompassed all societies and associations, including political parties, of the time.

This is why Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei appears as a perfect subject to study. It embodies the aspects of both Western modernity and Japanese tradition. Examining the work and thought of the composers reveals different compositional techniques and motivations that range from the defense of Japanese culture in the Westernized society to the idea of renewing expression in Western art music by elements from Japanese music. To give you an idea of what this all meant musically, I would next like to present some examples.

We will start with the composer Shūkichi Mitsukuri (1895—1971). His approach to Japanese-style composition was to create a new harmony theory, which he called ”Japanese harmony” or “East Asian harmony”. The reason for this approach was that as harmony was such an important element in Western music, but did not exist in most genres of traditional Japanese music, a Japanese harmony system would be the most profound synthesis of Western and Japanese principles.

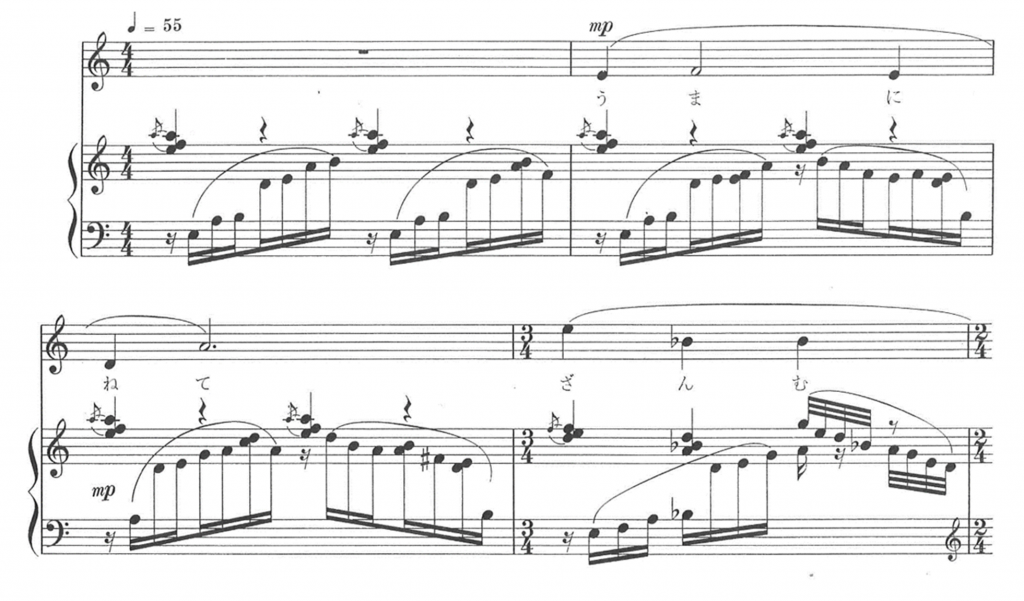

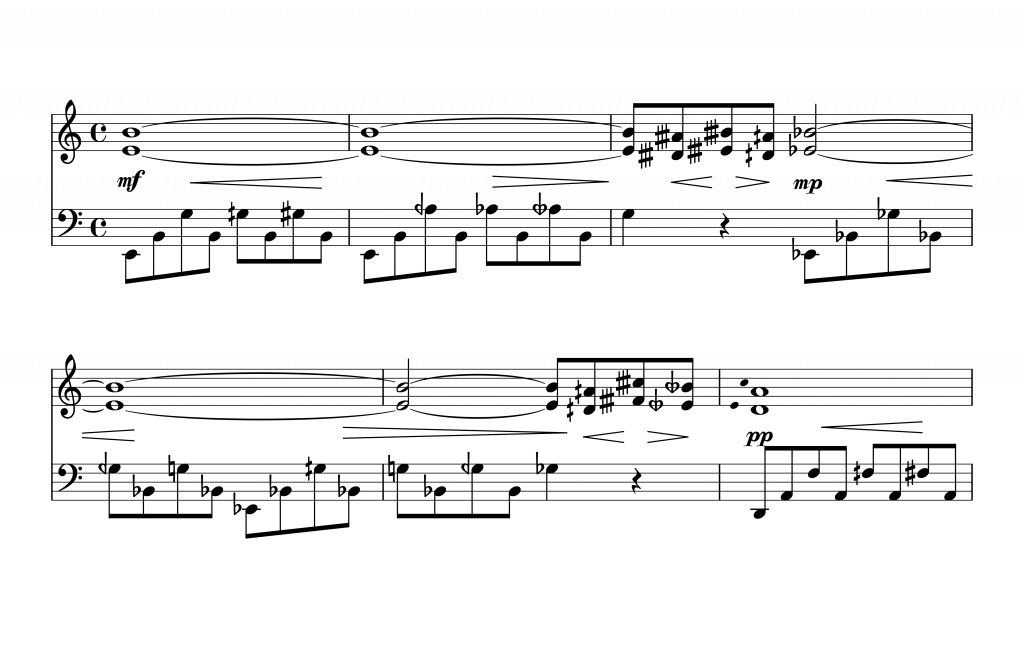

Mitsukuri’s most well-known work of this kind was Bashō kikōshū, or Collection of Bashō’s Travels, which he composed in 1930—31. It is based on ten haiku poems by Matsuo Bashō, a poet of the 17th century, who is one of the most well-known poets in Japan. In the second song, for example (ex. 1), Mitsukuri modulates between different keys of his tonality system to convey aspects of the poem, namely different levels of consciousness, and different levels of distance; in this case, between being awake and being in dream.

© Zenon gakufu shuppansha

The song follows the overall miniature nature of Bashō’s poem. Audibly, however, most of Mitsukuri’s works following his harmony theory do not resemble any distinctive genre of traditional Japanese music. Rather, he sought to create a new language of music — or, a Japanese idiom of composition — by fusing Western and Japanese principles on a theoretical level.

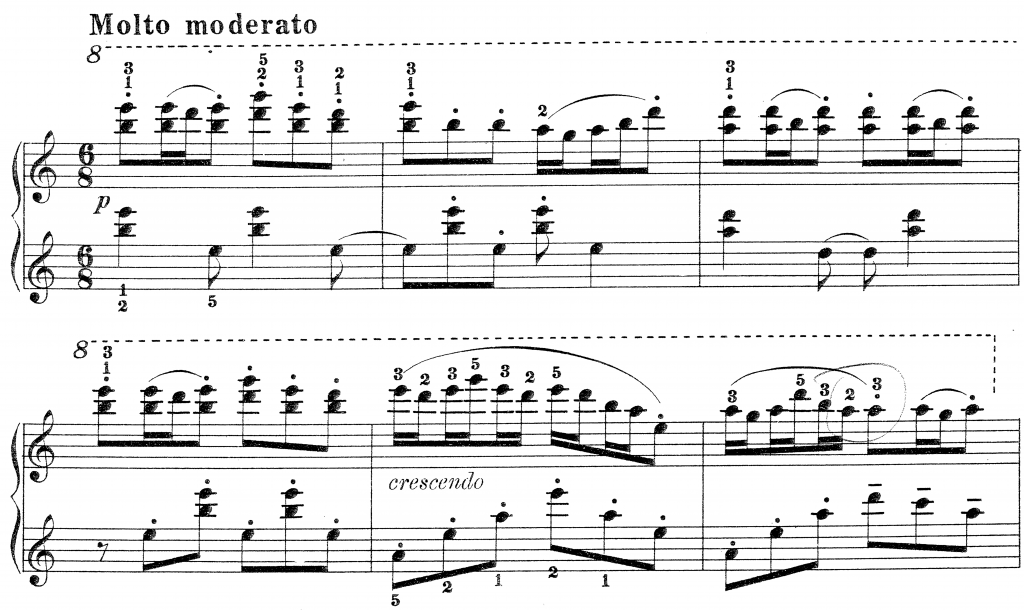

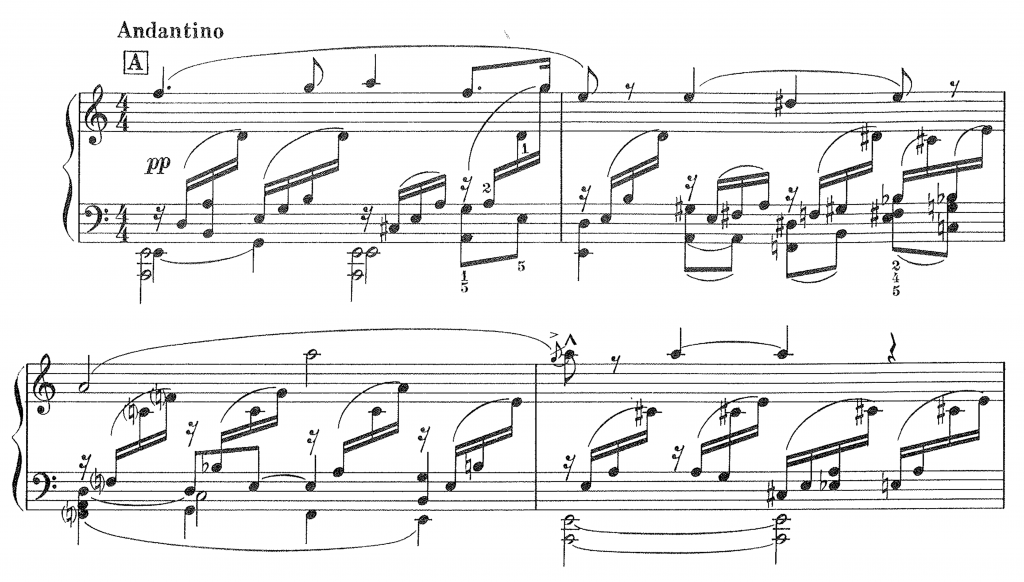

The approach of creating a Japanese idiom of composition was represented also by Yasuji Kiyose (1900—1981), who is best known as the teacher to Tōru Takemitsu. A good example of this is the piano work Oka no haru, or Spring in the Hills (ex. 2). Kiyose considered the use of pentatonic scales of Japanese music as the best way of creating a Japanese idiom of composition. And indeed, this piano piece utilizes a scale of traditional Japanese music, and, in a sense, follows what we could call Japanese tonality rather than Western one.

© Edition Alexandre Tcherepnine

Kiyose did not only adopt scales, however, but also utilized them in a way that suggests that he was deeply informed about the use of scales in traditional music — although a consistent theory of them did not exist at the time. He is also a good example of a composer who wished to contradict the hegemony of Western influence in Japan in musical means by Japanese-style composition, as his relatively ideological writings reveal. Although his compositional style does not appear as particularly modernist to us today, it was however the use of pentatonic scales that Kiyose himself found a “modern” approach in the context of Western art music.

The goal of developing expression in music by Japanese elements is also suggested by Kunihiko Hashimoto (1904—1949). A perfect example of this is Mai, or Dance, a song from 1929 based on a poem on a performance of a kabuki play (ex. 3). It contains atonal sections and even Sprechstimme, which was very unusual in Japan of the time and earned Hashimoto the reputation of an avant-garde composer. Hashimoto did not use Sprechstimme only as a modern element; it also connects with the kabuki theatre, which the original poem is based on. Kabuki has a recitative type of singing resembling Sprechstimme, so it is actually both a modern element and a Japanese element at the same time.

© Zenon gakufu shuppansha

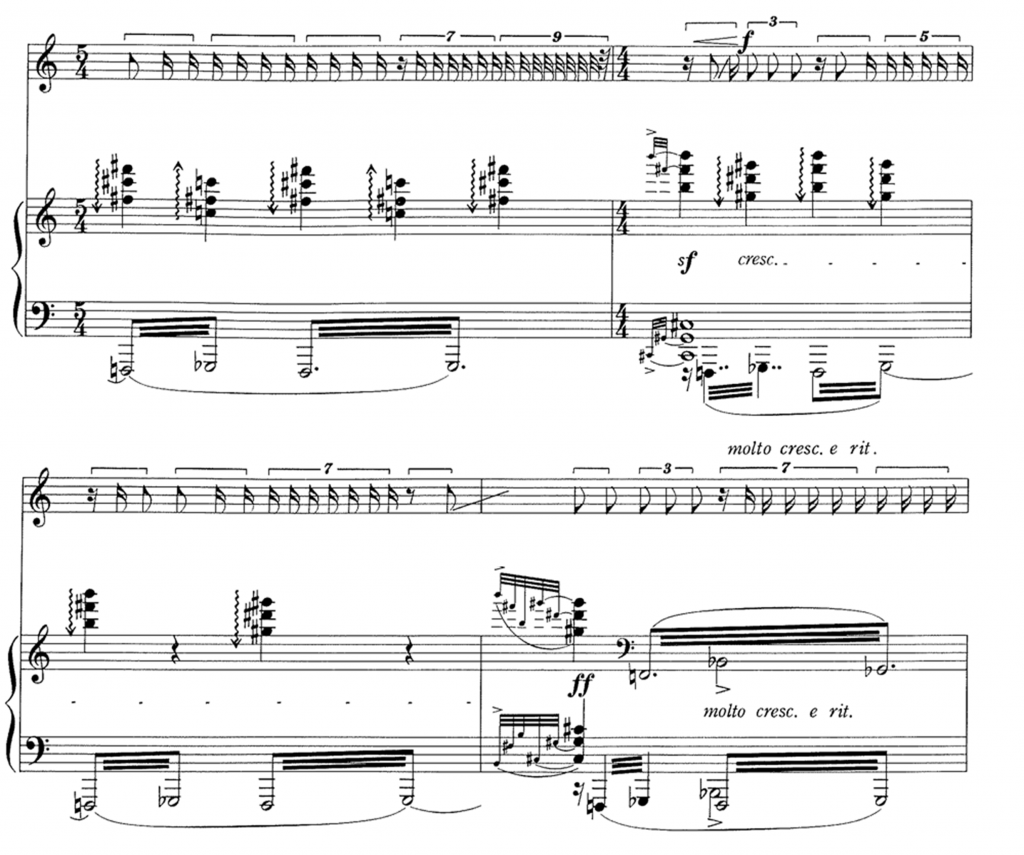

Another similar example in Hashimoto’s work is Shūsaku, or Study, for violin and cello, dating from 1930 (ex. 4). The work is microtonal and as such represented, once again, an avant-garde approach in the 1930s. It was thus mostly met with bewilderment. According to Hashimoto himself, however, he ended up adopting microtonality after noticing that Western staff notation was too limited to express subtle nuances of Japanese folk songs. In other words, here, as well, we encounter the aspect of using Japanese elements as modern expression — in a musical language that was truly modern also in the West. Of course, it could be that Hashimoto encountered microintervals originally in Western music and simply used them as a ”Japanese” element after this. However, even in this case, Hashimoto’s works are some of the very first examples of recognizing similarity between traditional Japanese music and expression that was modern even in the West.

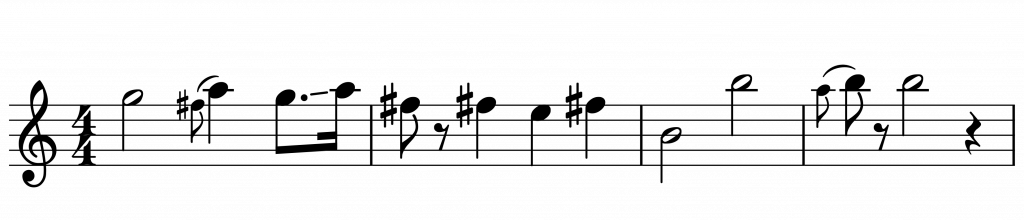

Finally, I would like to give one more example of a different approach, this one by Yoritsune Matsudaira (1907—2001). He typically quoted melodies of Japanese music but combined them with an accompaniment that disassociates them from their origin; in a sense, conceals them. There are many examples like this, but the one that I would like to present here is the solo piano work Riido ni — Ritsu senpo ni yoru, or, Lied deux — sur le mode ritsu (ex. 5).

© Zenon gakufu shuppansha

To me, this sounds like something that could have been composed by French Impressionists, or French modernists, and does not really evoke a distinctively Japanese mood. However, the melody is actually based on a very well-known piece of Japanese music. As you can hear, the melody in Matsudaira’s work is actually based on the Japanese court music gagaku, and a piece called Etenraku (ex. 6). It is the most well-known — and most often performed — piece in the gagaku repertoire. However, Etenraku in the banshiki key — which is the one that Matsudaira quotes — is different from the more commonly known version in the hyōjō key. Based on Matsudaira’s writings, his most important aim in this approach was simply to connect music with its geographic origins — namely, Japan.

While being only few examples, I believe that these suffice to demonstrate that there were different aspects to Japanese-style composition before the war. It was not as ”simple” or ”homogenous” as some previous studies claim, but rather introduce even relatively modern compositional ideas, although this is typically claimed to have originated only in the postwar period.

In many cases, the ideas that were considered especially ”Japanese” in the 1930s are — to some extent — different from what was considered so in the immediate postwar period, or today. This emphasizes the changing nature of these ideas and the changing perceptions of what can be thought of as ”Japanese,” and it thus connects also with the more general perceptions of the roles and images of Japanese culture during different time periods.

What I would most like to emphasize is that although the composers write that the origin of their artistic expression was solely in the need of modernizing music, I claim that it was also about a search for a national identity both in a national and international context, when examined against the social situation of the time. As my opponent, Professor Wade kindly pointed out to me before, composer Akira Nishimura (b. 1953) recently claimed that Japanese composers seriously began to search for their own identity only the in the 1970s. Based on the results of my thesis, this simply is not true, as this search began already before the war, and in some senses, goes on until today.

And this, again, comes back to one important theme: it emphasizes the idea that these musical works and artistic ideas also reflect and construct Japanese culture of the time. It was what could be called the musical constructions, musical communication, and musical representations of Japan in the work and thought of Shinkō sakkyokuka renmei.

**

This text has been modified from the original lectio praecursoria: comments referring to the PowerPoint presentation shown with the talk have been removed and substituted with the information included in the presentation.

Music examples:

Hashimoto, Kunihiko 1930. Shūsaku / Etude No. 1. Unpublished manuscript; viewed as microfilm at Archives of Modern Japanese Music in Meiji Gakuin University, Tokyo.

—2009. ”Mai.” Words Sumako Fukao. In Hashimoto Kunihiko kakyokushū 1, edited by Fumiko Yotsuya. Tokyo: Zenon gakufu shuppansha. Pp. 86—99.

Kiyose, Yasuji 1935 [1932]. ”Oka no haru.” In Modern Japanese Piano Album. Tokyo: Edited by Alexandre Tcherepnine. Pp. 2—4.

Matsudaira, Yoritsune 1991 [date of composition unknown]. ”Lied II (sur le mode ”Ritsu”).” In Yoritsune Matsudaira: Oeuvres pour piano. Tokyo: Zenon gakufu shuppansha. Pp. 52—53.

Mitsukuri, Shūkichi 1971 [1930]. ”Uma ni nete.” In Mitsukuri Shūkichi kakyokushū, edited by Uchida Ruriko. Tokyo: Zenon gakufu shuppansha. P. 43.