Introduction

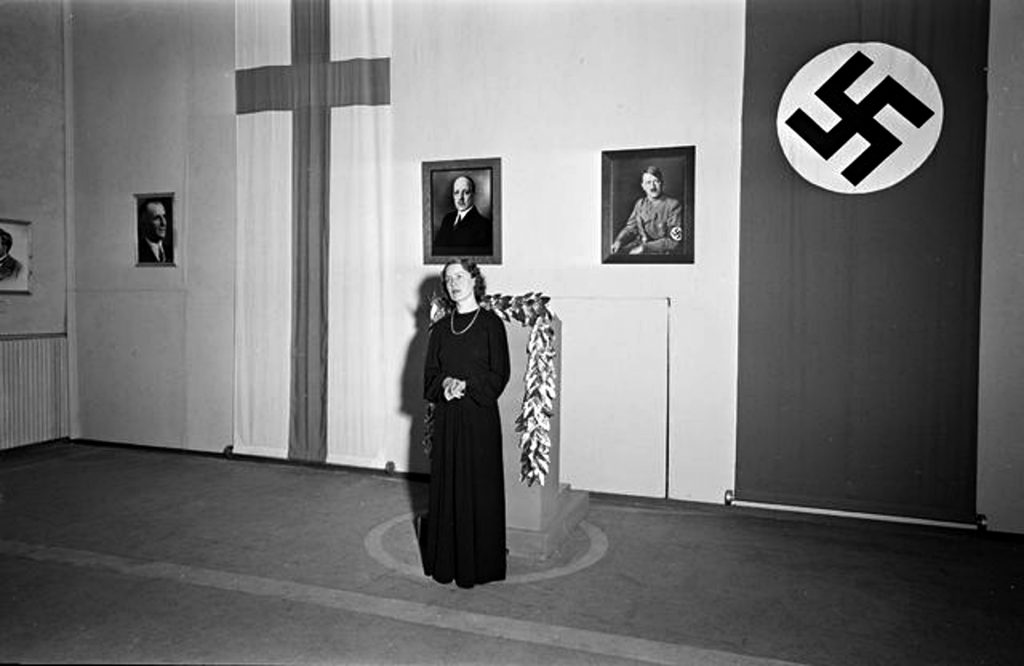

Finland and Germany have a long history of close bilateral relations. One concrete example is that German military actively took part in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, on the victorious White side.1 In the Second World War (WW2) Finland fought as Nazi Germany’s Waffenbrüder (brothers-in-arms) against the Soviet Union 1941-1944 (Figure 1). However, the allies ended up as enemies at the end of WW2, in the so-called Lapland War (1944-1945), after Finland had made a ceasefire with the Soviet Union in September 1944. During the years that Finland and Germany fought together, Finland was presented in various ways for the German audience by both Finns and Germans.2 This included, for instance, scientific studies aimed specifically for the German audience. Many of these were designed to provide logical foundation for the Finnish occupation of Russian Karelia, based on the Finno-Karelian “tribal ideologies” and “Greater Finland” policies,3 and to support intended Finnish post-war claims on the conquered parts of Russia, as well as on parts of northernmost Norway.4 Scholarly contributions included such volumes as Finnlands Lebensraum (literally “Finland’s living space”) by Professor of Geography Väinö Auer and renowned historian Eino Jutikkala,5 Die Ostfrage Finnlands (“Eastern question of Finland”) by Professor of History Jalmari Jaakkola,6 an edited volume in the geographical journal Fennia “Anteil der finnischen Forscher an der Erforschung von Kola, Ostkarelien und Ingermanland” (“Contribution of Finnish researchers in the Kola, East Karelia and Ingermanland research”),7 and Muinaista ja vanhaa Itä-Karjalaa: tutkielmia Itä-Karjalan esihistorian, kulttuurihistorian ja kansankulttuurin alalta (“Ancient and Old East Karelia: Studies on the Prehistory, Cultural history and Folk Culture”) written by well-known geologists, archaeologists and ethnologists.8 The last was never properly published as the German fortunes of war started to change, and only a correction print of it exists in the archive of National Heritage Agency.

The book we focus on in this paper, Suomi kuvina. Das ist Suomi. Finnland in Bild und Wort (“Finland in pictures. This is Suomi. Finland in pictures and words”; henceforth Das ist Suomi), is a popularly oriented wartime presentation of Finland for a broad German audience. It was published in 1943 in both Finland and Germany, and offers a concise pictorial, thematic representation of the country.9 We discuss the various ways in which Finland is introduced to German audiences in the book, and study, on the one hand, the stereotypical representations of Finland through time, and on the other, the deviations from these “norms”, specific for the wartime conditions and propaganda. One dimension we explore is the gendered aspects of the pictorial representation, for instance, how Finnish and Sámi women are staged in certain contexts.

Several studies on national landscapes and symbols have examined how Finland and its national characteristics are pictorially represented for foreign and domestic audiences alike, both in the context of war and more broadly, and how certain imagery is used in the construction of the nation. Häyrynen and Ylimaunu, for instance, demonstrate the militarized aspects of visual representation regarding landscapes and people – especially men – in the 1930s.10 Valenius, on the other hand, has addressed nationalist and idealized portrayals of the female figure by examining the representation of the “Finnish Maiden”, the virginal personification of Finland, who Finland and Finnish men are supposed to protect.11 These studies illuminate the continuities of national imagery, while also pointing out that certain types of representations are specific to certain periods, such as wartime. Kleemola and Honkaniemi, on their part, have examined the works of the Finnish Army’s Information Company photographers and the utilization of their photography in recurring propaganda themes in various international contexts.12 This paper contributes to the growing interest in photography as the focus of historical and heritage studies in Finland, and also more widely.13 We seek to draw on these studies to scrutinize the pictorial representations of Das ist Suomi from the point of view of wartime propaganda and ideologies, asking how these manifest in a popularly oriented photographic book. The visual analysis of this kind of photographic propaganda permits new perspectives on Finnish society during wartime, and on the interaction between Finland and Germany during and after WW2. Images can be a very sensitive instrument in the study of societal change and fruitful in the examination of continuities and changes in nationalist conventions.

We approach the pictorial representation through visual analysis, more specifically using content analysis and a multimodal reading of images and their captions. Content analysis seeks to quantify the different components in an image and study their frequency in the publication or publications in question. Defining different variables in images, such as the gender of an illustrated person, enables comparative analysis between these featuring elements. Content analysis is best suited to examining volumes of images, that can be processed in tables as it is essentially a calculation of image content.14 The inclusion of a social-semiotic multimodal perspective allows the investigation of more complex symbolic messages in the illustrations, their captions and their contextualization. The picture-text combination is treated as one unit where all parts are of equal importance and together form a coherent message. The framing, angle, salience, distance, and setting of a picture, for instance, are all catalogued and cross-compared with the predetermined picture elements, potentially yielding significant recurrences.15

Olympic Stadium, during the three countries’ athletic games in Helsinki in 1940 (Photograph: Helsinki City Museum N16210; Pietinen Aarne Oy, Helsinki 1940; CC BY 4.0); these games are

illustrated also in the book Das ist Suomi (Suova 2 1943a, 231–232). Olympic Games were supposed to be in Helsinki in 1940, but this was stalled by the war.

Finland in pictures Book Series 1929-1951

Das ist Suomi is a bilingual (Finnish-German) popular photographic book, which presents Finland, its people, landscapes, and livelihoods for the German public. It is part of a series of several multilingual photographic presentations of Finland published in 1929-1951. The earlier editions16 presented Finland with large images in geographical order from south to north, in different editions with different languages: Finnish, Swedish, English, German, French and Italian – the second edition from 1930 in all six tongues.

Later editions, edited by Maija Suova,17 rely on thematic chapters and are more dynamic in their layout -the earlier editions had only one photo on a page. There are also more images of people and various activities taking place. The 1943 edition was published as a bilingual Finno-German edition in Finland18 and as a German language edition in Germany.19 Even if it is not an actual tourist guide, there are references to recreational activities and touristic experiences in the book. The Central European-like sceneries are emphasized, for instance, Aulanko forest park in Hämeenlinna, sailing in Turku Archipelago, boat rides in the Lake Saimaa region, and white-water rafting in the rapids of Oulankajoki, supposedly appealing to the German audience.

The illustrations are of an outstanding quality, and overall, the book presents Finland in the best possible light. Used imagery is in fact very much similar to the present-day, early 21st century travel and tourism promotion images.20 As has been, and is, typical in Finnish tourism imagery, a strong emphasis is placed on nature. Along these lines, the captions, on their part, serve a clear purpose of underlining those aspects of Finnish history and landscape that would be easy to identify with for the intended German audience. An example of this is the aforementioned Aulanko forest park, which was modelled as an English-style landscape garden in the early 20th century,21 but described in the book as “bringing in the mind the lush Central European parks”. Presumably describing the feeling of the park as Central European in a caption was deemed more appealing for the Germans, who were at war with the United Kingdom.

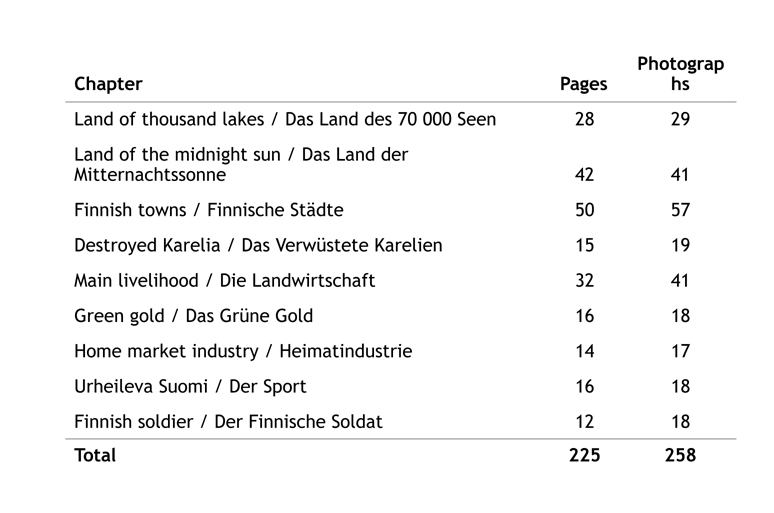

Although the book is not official propaganda, the period of war is very visible in the themes of the images. Many of the photographers in this book, such as Björn Soldan, Pekka Kyytinen and Otso Pietinen, in fact served as Finnish Army Information Company photographers. Their work is typified by examples of propaganda-oriented illustrations, such as the widespread destruction caused by the Soviets to Finnish heritage, especially religious sites, in the ceded Karelia during the so-called Interim Peace (1940-1941) (Table 1), as well as examples illustrating martial aspects, such as the capability and character of Finnish soldiers (Table 1). These images and their captions touch upon recurring themes which were widely used in the official war propaganda directed for the foreign audience.22 The book is a clear representation and reiteration of the friendly Finnish-German relations, although by 1943, when the book was published, the official relationship between the two countries was starting to falter.23 The Germans had not made any significant progress in their war efforts in the Eastern and Northern fronts, and the Finnish military officials and government were beginning to realize that Germany would lose the war against the Soviet Union.

each chapter.

The book also features landscapes from the Finnish-occupied Russian Karelia, so-called East Karelia, the Finnish Lebensraum-to-be, which had been one of the foundations for building a Finnish national identity since the 19th century.24 Karelianism refers to an ideology according to which the Finnish cultural roots in their most authentic and primitive form were thought to be found in Karelia (currently in NW Russia). It inspired a cultural movement that involved scholars, writers, painters, poets and sculptors searching, studying and recreating an imagined past for Finland.25 In this perspective Karelia includes both the so-called Finnish Karelia, most of which Finland had to cede to the Soviet Union after the Winter War (1939-1940), and East Karelia, which has never been officially part of the Finnish state but was the target of several Finnish military expeditions in 1918-1922 and was occupied by Finland in the Continuation War 1941-1944.26 However, by 1943 creating a Greater Finland was already a fading dream. These expansion plans stemmed from nationalism and state-sanctioned ideology of the young country that sought to unify its peoples after the Civil War of 1918.27 Das ist Suomi refers to Karelianism in many ways, but perhaps the most overtly visual representation of this theme is the back cover of the book, where a map of Finland and East Karelia has been attached in a separate fold-out leaflet illustrating the pre-war borders; thus East Karelia is not contained within the Finnish state borders in the map. Interestingly a post-war reprint of the 1943 Das ist Suomi was published in 1946. Rendering the changed political conditions, in that edition the section “Finnish soldier” was omitted. Nevertheless, the nostalgic chapter on “Destroyed Karelia” (illustrating the areas ceded to the Soviet Union first in 1940 and then again in 1945) and a map still showing Finland’s pre-war borders and East Karelia, were included.28

The Maiden of Finland

The book cover presents a photograph of a young woman dressed in a Finnish traditional, national folk costume, sitting on a fence by a swaying field of wheat. This connects with the commonly used personification of the country as the ”Maiden of Finland” in fine arts and also elsewhere, such as in satirical cartoons and postcards.29 The idea of using a female figure as a personified mythological symbol for an area has its roots in Antiquity, and experienced a European renaissance from the 17th century, in Finland also.30 The Maiden of Finland dressed in a national costume became established as the symbol for the country from the 1880s, and sets the tone for the whole book, which draws heavily from the established national romantic imagery.31 However, many of these references were probably missed by the German audience unfamiliar with the Finnish national romantic ideals.

National identities exist always as representations, or ideas, that vary in time.32 Creating a characteristic Finnish identity during this period was largely about making a distinction between Finland and its pre-1917 rulers, both Sweden and Russia. In the early twentieth century, when Finland witnessed intense political struggles for its independence from the Russian Empire, there were many competing representations of the embodiment of the emerging Finnish nation.33 Among the different groups, the socialists promoted a female figure dressed in simple dress without national insignia, and the royalists, who wished that Finland would follow the model of democratic Swedish Kingdom, favoured an image of a maiden dressed in bear skins, connoting ancient Nordic mythology. Contradictions and divides within the nation are typically unified through the use of political power,34 and the ideology of creating a distinct Finnish culture and identity won over these suggestions. Thus, the political forces driving the independent Finnish nation preferred a maid in a national Finnish dress.35 It is notable that the Finns chose not to emphasize Swedish ancestry or the remaining ethnic minority in Finland, which could have made them more readily accepted as part of the “Nordic race”.

Ethnologists remind us that the national costumes are re-constructions produced for specific ideological purposes.36 In Finland, they vary according to regions, and can be roughly divided to Eastern- and Western-style dresses. The Western-style Finnish costume that the woman in the book’s cover wears came to dominate the images after Finnish independence in 1917. Propaganda of the newly independent state emphasized the departure from the stereotypically archaic “East”, represented by the former Russian colonizers, and attempted to identify with the modern “West”. The blonde girl in the book cover also mirrors the devoted attempts to overcome feelings of national inferiority, and to establish a national identity and self-esteem as part of the western world. Finns had been, after all, for a long time branded by the racial theorists, such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840) and Arthur de Gobineau (1816-1882), to be part of the weak “yellow race”.37 Such views were familiar and supported in the Third Reich, and basically excluded the Finns from the Aryan race.

However, Finnish women were selected, much to a national pride and surprise, three times as Miss Europe in the 1930s (1934, 1937 and 1938).38 When Miss Europe 1938 Sirkka Salonen, who is also illustrated in Das ist Suomi wearing a folk costume on a field, was interviewed for the state radio, she said that she wanted to prove to Europeans that the “Finns are not slant-eyed Mongols”.39 Thus the emphasis on the stereotypical blonde and blue-eyed beauty of the Finnish girls throughout the book obviously attempts to substantiate to the German audience that Finland is part of the “West” (Figure 2).

“Land of 70000 lakes”: National landscape in 1943

Since the late 19th century, the Finnish national landscape has been based on illustrating three major elements: hills, water and forests. The images in Das ist Suomi harness a familiar nationalist imagery with emphasis on rocky inland lake sceneries. Establishment of these kinds of sceneries has its roots in the so-called “Topelian” landscape imagery – referring to Zachris Topelius, 1818-1898, a famous Finnish author, patriot, and essentially the inventor of the Finnish national landscape (and also rector of the Imperial Alexander University of Finland, now the University of Helsinki).40 These, nowadays clichéd, inland lake scenes became established as the iconic Finnish landscapes from the mid-19th to early 20th century,41 and their solitude and serenity were described by poet J. L. Runeberg (1804-1877) as divine manifestations.42

The photographs in this book touch upon several familiar, long-term pictorial traditions in Finnish national imagery, and play on the sublime quality of the landscape with grandeur and dramatics. The national landscape of Koli Hill in eastern Finland, for example, makes a frequent appearance in Finnish landscape representations, especially since the late 19th century in the spirit of “Karelianism”.43 The images underline the depth and contrasts of the landscape with a dynamic interplay of light and dark shades, which promote a sense of drama. This is within a well-known pictorial tradition of “the picturesque”, which emphasizes the vastness and “wildness” of landscapes.44 The illustrations do not shy away from the danger of this magnificent landscape, which “God has carved”. The natural world and forests with no traces of human influence, for example, have long been a source of reverence in Finnish sentiment, especially in the elitist culture, which looked at the landscape not from the perspective of work but refreshment, unlike the rural working-class living off the land.45 The images are an apparent imitation of the visual style produced from the late 18th century onwards, from Zachris Topelius’ Finland framställd i teckningar to the photographs of I. K. Inha in the late 19th century, and represent practically all of the tendencies of the national imagery from the late 18th to mid-19th century.46 During the invention of the national landscape, the Finnish nation was still in search of its historical roots and thus turned to nature. Although the understandings of Karelianism provided temporal depth for the nation, the landscape imagery persisted from the earlier Topelian origins.

Lakes are also a major foundation of Finnish landscape imagery. This is referenced already in the opening pages of the book, which titles Finland as the “land of a thousand lakes” – or in German the “land of 70000 lakes”. Birds-eye-views of topography that mixes lakes and forests are prominent, and in no way deviate from the norm of earlier representations of the nationalist landscapes. For instance, the renowned Punkaharju Esker is described in the book as a poetic landscape in which “nature itself sings as the sun glimmers in small mazes of lakes, onto which slim straight pines are reflected”. The pine is another national emblem, which represents the firm roots of Finnish nation defying outside threats.47 Since the invention of the national landscape, this threat has originated from the east. In the context of war, the firm foothold against the Bolshevist Soviet Union is of special emphasis and sturdy pines feature in most of the landscape images. In Suursaari, which the Soviets occupied during the Winter War, a lone, thick pine is pictured standing alone in the middle of the image surrounded by rocky hills, emphasizing its nature as a rooted Finnish landscape and a guardian against the East (Figure 3). Suursaari was considered as part of the established Karelian landscape,48 and this image harnesses the well-known iconography of one of the famous masterpieces of Finnish nationalistic art, Eero Järnefelt’s (1863-1937) “Scenery from the Koli Hill” (Maisema Kolilta, 1928).

The context of war is peculiarly attached to the descriptions of these pure nationalist landscape images. In contrast to the poetic nature of the photographs, the emphasis in photo captions turns recurrently towards the enemy and their inability to cope in the Finnish nature. Nature itself appears to participate in Finnish warfare as an ally, and on many pages, the Finnish landscapes are referred to as insurmountable obstacles and barriers for the enemy. The Lake Vuoksi in the Karelian Isthmus was an “undefeated obstacle” for the Soviets in the Winter War, and the shores of Gulf of Finland are “unwelcoming for the enemy” with their rocky terrain. The emphasized difficulty of the Soviets when moving in the Karelian landscape, and in contrast the ease with which the Finns roamed about, underlines this area’s Finnishness.

Karelia is a typical borderland space between Finland and Russia, and involved in several struggles between these states for its control prior to and throughout the period of war.49 The idea of Finland as the last outpost between Russia and the western world originates from the 19th century and illustrates the political pressures that small countries faced, especially in the first half of the 20th century.50 The emphasis on the eastern borderlands in Das ist Suomi represent these ideas, and the symbolic significance of Finnish Karelia as a boundary between the East and the West is emphasized. Karelia is represented as a buffer zone against the east and “separated from the rest of Finland by Lake Saimaa”. On the one hand, Karelia was considered an authentic Finnish landscape while, on the other, the Karelian border between Finland and the Soviet Union represented a line across a dangerous periphery from which eastern influence had to be eradicated.51 Thus the Karelian landscape had to include the right kind of Karelianism, from which, for instance, the orthodox chapels were excluded as they were considered to be too Russian in character.52 The Karelian landscape also features as a destroyed landscape, both in the built environment and the natural surroundings. The book has several images of the battlefields of the Winter War (1939-40), with dead trees (Figure 4). The dead tree-symbolism enabled the representation of human suffering and the gravity of war without having to resort to actual images of dead bodies, and this visual tactic is in fact still deployed in history books.53

“Ruhr of Finland” and “Paris of the north”: Southern and northern settings

Modern factories, mostly in southern Finland, were an integral part of the Finnish landscape at the time. However, in the book their seamless connection with the surrounding nature is emphasized, and the factories are described as enhancing their natural environs instead of polluting or destroying them. The factory workers, much like their rural counterparts, are represented as staying in touch with the nature where the strength and health of Finns originates. The clash between modernism and naturality is faded in the captions, although in the images it is obvious with the white modernist factories against the natural surroundings. The book illustrates a nation that is modernizing but wants to contain the relationship with the natural world, and hints at conflicting emotions between primitivity and industrialization. Since the late 19th century technological progress was met with contradictory emotions, and a romantic sentiment existed in Finland towards the pure wilderness setting.54

Northern Finland is illustrated in its own chapter, the second longest in the whole book, with altogether 41 images. This was likely considered important for the target audience since the German war efforts in Finland were mainly focused in northern Lapland. Germans also presented their own take of the Lapland landscapes to the German home audience, for example with author Mabre’s coffee-table book Fahrbahn Lappland (“Lapland’s roadway”), but the feel of that book is quite different from the Finnish perception.55 Das ist Suomi takes on a more sublime reading of the arctic area, focusing on the grandiosity of the Lapland landscape unlike Fahrbahn Lappland, which renders Lapland somewhat gray and dreary.56 Since the early modern period, Lapland has been portrayed in two conflicting traditions: on the one hand, there is a more somber and dystopian perception of Lapland as the extreme northern periphery of the European world, and, on the other, a view of it as an enchanted land of exotic natural and supernatural wonders.57 If Fahrbahn Lappland’s take on the arctic front was leaning more towards the dystopian side, Finns themselves captured the exotic and magnificent character of Lapland, its majestic landscapes with a truly awe-inspiring feel. The illustrated houses also seem a bit more habitable and less desolate in comparison with the German portrayal, and the exotic wonders of the North such as ice flowers, the midnight sun, and transport by reindeer are mentioned. This portrayal of Lapland originated already from early works such as Voyage Pittoresque Au Cap Nord58 from the early 19th century, illustrating the dramatic and grandiose Lapland with its signature fjells and rapids.59

Although the national imagery, already put forward by Topelius, created a common distinction between the sublime wilderness of Lapland and the civilized south,60 Das ist Suomi appears to tap into both the modernity and primitivity of Lapland. The primitive beauty of the landscape is contrasted with the modernity of Lapland, which is most notably brought up with images illustrating the capital of Lapland, Rovaniemi, dubbed as the “Paris of the North”. A classic example of this is the Hotel Pohjanhovi, which represents the modern architectural functionalism of the 1930s (Figure 5). It was also a favourite hang-out of German soldiers during the Continuation War, and thus might have been familiar for the German audience.

The roads are very visible in the photographs of Lapland’s landscape, and all seem to be in a good condition for passenger cars to make their way along the so-called Arctic Ocean Road (Eismeerstraße) to its northernmost point Liinahamari on the coast of the Arctic Ocean in Petsamo. However, in reality Lapland’s infrastructure and road network were very rudimentary during the war, which hindered the German war efforts in the north and forced them to concentrate on large infrastructural projects behind the frontlines with the Prisoner-of-War and forced labourer workforce.61 The wartime marked a significant increase in the northern infrastructure, owing much to the German operations, and the Arctic Ocean Road from Rovaniemi to Petsamo was also of key importance as an artery of transit for the German troops. As another example, the road leading to a functionalistic hotel built high on the Pallastunturi Fjell, and its own, rare electric station in the middle of nowhere, are brought up, again emphasizing the apparent modernity of Lapland. The presentation underlines these comforts in the middle of wild Arctic landscape for the Germans, prospective post-war tourists.

During the 1940s characteristic Lapponism, the era of admiration towards the Lapland landscapes and nature, Europe’s only indigenous people, the Sámi, were not considered proper motifs, for instance, for art, as artists wanted to seek and emphasize similarities of the north to the rest of Finland, not the differences.62 The Sámi are illustrated in the book in only two images, one featuring Sámi men and the other one woman and several children. In the images, the men are looked down upon as the angle is high, but the woman and children, on the other hand, are viewed from a level angle; the high angle has been referred to as an illustration of the photographer’s power or superiority over the photographed subject.63

The wealth of Lapland and the “Lapps” [sic] is underlined through the illustration of fishing and reindeer industries, and the captions refer to the salmon rich waters of the north, log industry and the wealth of reindeer herders. The book has a slightly assertive attitude when it comes to illustrating the “Lappish” folk, though. The Sámi children and men appearing in the images are described to “belong to an arctic race but have adopted a Finnic language thousands of years ago and are the racial relatives of the Finns”. Curiously enough, in the 1951 version of this book, the caption is worded differently and states point-blanc that “the Sámi are not a Finnic race”.64 What changed so drastically in the sentiments in just the few years between these editions? In the post-war years, the Finnish State took a stronger hold of Sápmi, the homeland of Sámi people stretching across the northernmost Europe, and its natural resources.65 The Sámi were largely considered as a primitive “Other” and met with official integration politics. This included, for instance, establishing boarding schools where talking their own language was often forbidden from the Sámi children,66 and it was not until the 1960s that the Sámi were included in the official state iconography, such as postal stamps.67 The new photo caption in the 1951 edition thus fits with the state’s post-war interest in taking over Sápmi, by distancing its indigenous people from the mainstream Finns. The education and Christian belief of the Sámi are emphasized in the 1943 edition, but this is credited to the southern Finnish influence. For the German audience, the Sámi probably appeared as exotic “Others”. However, to some they might have been already familiar “Others”, since many Sámi were toured as attractions in various zoos and fairs in Germany, France and elsewhere in the first half of the 20th century.68 Another example of assertiveness in the Lapland illustrations is one image caption, which describes the setting of a downhill skiing slope and explains that on the fjell slopes “the birch trees resemble apple trees”, as if the alien landscape needs to be palliated as something more than it is with textual methods.

Primitivity is attached in this book also to the pictures of Karelia. The dominant religion amongst the people in Russian Karelia in the 1940s was Orthodoxy, and also Finnish Karelia had an Orthodox minority. The Orthodox landscape with its unique chapels and crosses was familiarized for the Finnish audience by the 1940s, for instance, through travel and literature. Prior to this, the Orthodox religion would have been considered a Russian cultural trait, but by the wartime it had become an exotic feature in the landscape, which reflected the unique quality of the Karelian way of life.69 It is debatable though, whether the appreciation of the Karelian way of life was shared mostly among the more sophisticated, elite supporters of Karelianism, or if the idea was more widely accepted in Finnish society at the time. The difficult experiences of the Orthodox evacuees from Karelia, who tried to settle down and integrate in the mainstream Lutheran society after the war suggest the first.70 Orthodoxy is illustrated in the book for the German audience also in the northern Petsamo, then part of Finnish Lapland. Petsamo had quickly become the focus of nationalist sentiments after Finland gained the region in the Tarto peace treaty in 1920, and especially after the Arctic Ocean Road from Rovaniemi to Petsamo was finished in early 1930s.71 An Orthodox monastery is mentioned in the book as one of the attractions in the area.

Orthodoxy was also used to represent the mixture of Christianity and folk traditions – a suitable mixture of civilized Finnishness and original, primitive Karelian culture. The praasniekka celebration illustrated in the book was one expression of this mix. If primitivity was considered as something negative in relation to the Sámi, it was presented as authentic and pure in the case of Karelia; it was the right kind of Finnish primitivity. In the images, the Karelian people are seen dressed in old-style clothing, playing ancient instruments, such as kantele and birch bark horns, and weaving traditional tapestry, ryijy, signifying their folk ways (Figure 6). These images reflect familiar trends in the arts and the primitive Karelian way of life features in many classic national romantic paintings, such as Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s renowned painting “A Herder boy from the Lake Paanajärvi” (Paanajärven paimenpoika, 1892).

“Finnish towns”: Functionalism and militarism

The book illustrates also some of the largest and most important cities in Finland. In the representation of these, weight is placed on the most flattering historical aspects from a presumed German perspective. Turku has the longest history of any Finnish town – a history, which is western-oriented with its international ports and medieval churches, manor houses and castles from the time of Swedish rule. In fact, the time of Russian rule is disregarded in the image captions altogether. For instance, the most visible symbol of the city of Helsinki, the Lutheran cathedral, is introduced by mentioning its German-born designer C.L. Engel (1778-1840), and not paying any attention to the fact that it was Russian Tsar Nikolai I who commissioned its construction. The entire Empire-styled centre, where the church is located, originates from the time of the Russian rule (1809-1917). The buildings from this period feature throughout the book, but in the captions no attention is paid to their period of origin or style. Also, the book mentions that Helsinki was established in 1550, but fails to mention when and why it became the capital in 1812, after the Russian Empire conquered Finland from Sweden. The architecture in Helsinki is a manifestation of Finland’s history as a borderland between the Swedish Kingdom and the Russian Empire. However, Finns strived to create their own history and national character. Hence the functionalist architecture in Helsinki is emphasized in Das ist Suomi, as was appropriate given that the style originated in the new and independent state of Finland.

Functionalism represented a pure, healthy and rational nation, in agreement with the broad National Socialistic ideals.72 Buildings such as the new post office (1938) and the military hospital Tilkka (1936) in Helsinki, or the aforementioned Hotel Pohjanhovi in Rovaniemi (1936) characterize the architecture of the 1930s, and hence illustratively emphasize the newborn Finland free of Russian influences.73 Also, the House of Representatives in Helsinki, which stands as a notable symbol of Finnish independence, is shown. These are all located in the newer parts of Helsinki, away from the original Russian-era Empire-style centre, and hence the book sidelines the city centre’s 19th century Russian architecture.74 Many other towns are illustrated as well, and the same themes carry on throughout with photographs of modern schools, churches, and factories, which are the foundation of the wealth and economy. Ports connecting Finland to the western economic sphere and linking Finland historically to Germany via the Hansa trade are also depicted, and, for instance, the caption describing the port of Helsinki mentions that it is connected straight to the German cities on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

These aspects, for instance schools and the House of Representatives, can also be viewed as landmarks for the values of the democratic Finnish society, which deviated from that of the target audience in Nazi Germany. It is noteworthy that Finland emphasized democratic, educational and religious values for a country under totalitarian rule.75 However, militarism is also visible in the cityscape. This military camp mentalism of Finland’s early independence-era and the orderly martial landscape of soldiers standing in squares is pictured with a photo of the Flag Day parade in front of Helsinki Cathedral.76 This martial framing also includes several monuments in the cityscapes that commemorate the Finnish Civil War (1918), between the right-wing Whites and left-wing Reds. All the illustrated statues are for the victorious White troops, who won the war with the aid of the German expeditionary forces. Any traces of the socialist Red troops are noticeably obliterated from the landscape in this context, although memorials for the Red troops had already been commissioned early on in WW2, as an attempt to acknowledge their memory and integrate them in the collective and uniting war effort.77 Militarism is visible in the cityscapes in other ways as well, for example in the illustrations of historical castles from the eastern regions of Finland. These reference military power and represent Finland as an enduring symbolic stronghold against the east.78 The captions mention that Olavinlinna in the town of Savonlinna, eastern Finland, has been a protection against the invading Russians, and that the Viapori (Sveaborg) Fortress in Helsinki (now known as Suomenlinna) is a guardian against the East. All the illustrated castles are connected to the sphere of western history, since they were built under the Swedish rule before 1809. The imagery in question is in line with the official imagery originating of the 1930s’, which narrated visions of a democratic nation unified by military defence.79

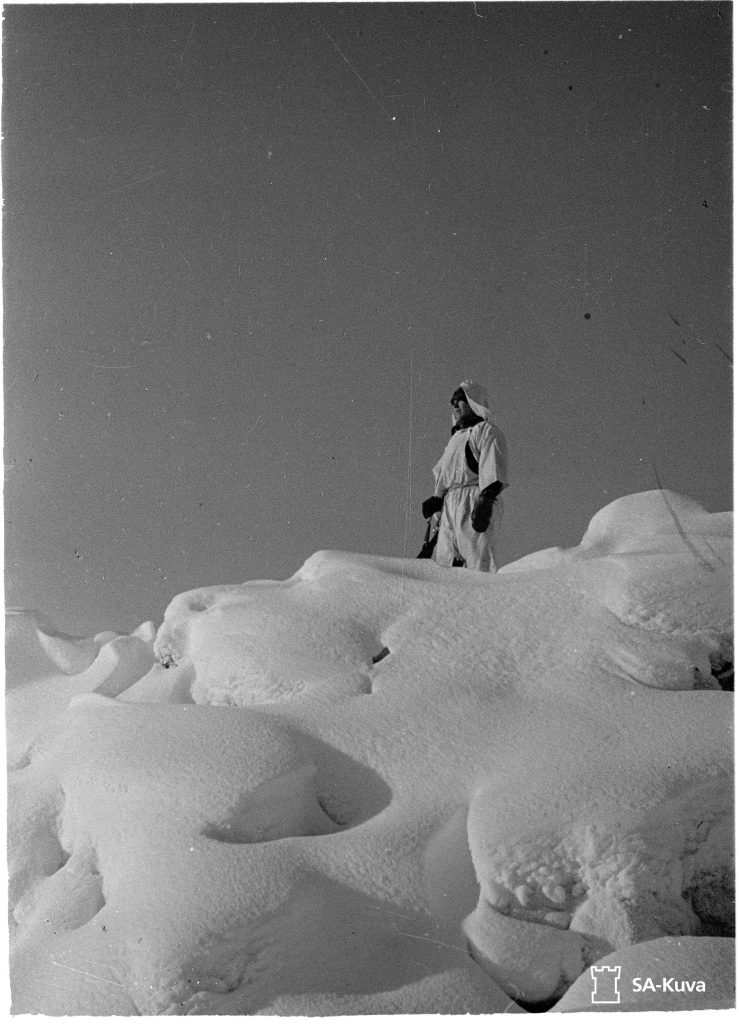

“Finnish soldier” and “Main livelihood”: Men, women and gender roles

Traditional Finnish nationalism, sometimes referred to as “agrarian nationalism”,80 is on the foreground in this book, and also reflected in the way that people are portrayed. The wartime context affects especially the representation of men. They are essentially pictured as soldiers who sacrifice their lives for the nation and the Fatherland.81 The Finnish soldier was supposed to be vigilant, and Finland the last outpost between the East and the West. Several pictures reference the image of soldiers standing on guard, and the last image of the book states in its caption that, “The Finnish man guards the border between the east and the west on the fjells of the North”.“North” with a capital letter (Pohjola) refers to Finland’s fabled setting on the northern fringe of Europe and carries connotations to the Finnish national epos Kalevala (Figure 7).

The Finnish soldier is presented as always ready and waiting, standing on the shores of Finland, which work in his favour and as his allies with their rocky terrain. He lives, first and foremost, close to and from the grand Finnish nature, and is a farmer and a warrior of the wilderness. He is illustrated as fighting his enemy using his wits in the wild, even if he is under-equipped, as was the case during the war, and with strong sportsmanship skills such as skiing. The Finnish man thus draws his strength from the interaction with nature, and therefore also the sports arenas are located in nature, such as the Vierumäki sports college pictured in the book.

The men are presented as “type figures” who are not engaging the viewer’s attention on a personal level. The origins of such illustrations stem from racial histories and colonialism, but rather than illustrating the otherness of the depicted, these images obviously aim at presenting the ideal individuals.82 The only soldier looking into the camera with a more individualistic expression is Marshall Mannerheim, the commander of the Finnish armed forces and the personification of Finnish militarism. In addition to being heroic soldiers, the working-class men are presented as achieving settlers – another elite tactic of portraying the idealized rural working-class people.83 In the opening chapter and the “Main livelihood” chapter this image is referenced by several pictures where the Finnish men are either clearing forests with axes, working in the fields or ploughing the soil. The portrayal of men reflects the sacrificial logic of nationalism, which gained momentum in the political atmosphere of the 1930s. It directed men towards what the elite and the state considered their proper duties, and the various ways to work and submit for the country:

Death is a part of the lively present, a gaunt but obligatory presence! Belonging to a battalion of death is the joyous and truly masculine duty of every man. Around the world the same phenomenon appears: in one way or the other women also want to participate in military service. Death is no longer a terrifying shadow cast over lives – the horrors of a narrow gate that need to be bypassed with every laborious effort during the day and occupy nightly thoughts. Death is not a punishment and reward of sin, but a calling. And the prayer of a soldier does not beg for mercy or atonement, but instead proudly requests: Teach me to die without remorse and complaint, as a man and fighter ought to!84

Throughout the book men are presented as active, engaging in various tasks, such as working and roaming in the wilderness, whereas women are only active at home, and when occasionally in the nature, they are gazing at it from a distance. The 1943 book version is perhaps surprisingly clear-cut when illustrating the different gender roles of men and women. Men are shown, besides soldiers, athletes and settlers, as educated chemists and biochemists working in the forest industry, the “Green gold” of Finland. However, in reality in the wartime women participated in the work that had been usually done by men, for instance in factories.85 They assisted also in the war efforts through the paramilitary Lotta Svärd organization, which was for example responsible for the food delivery, hospital facilities, and even airspace monitoring. Although women were very active in the society during the war, actively working women are referenced in this book with merely one image of a Lotta Svärd participant, a few images of women in agricultural activities and arts, and two images with female factory workers, the other from the famous Arabia porcelain factory. In comparison with men, women are far less active, and most of their activities in the book consist of household chores, doing handicrafts and sowing, baking Karelian pies, and studying domestic skills. Also, the activities of the main promoter of household ideology and training, The Marttaliitto (Martha Organization),86 is well illustrated in the book, since it appears to have been promoting the right kinds of roles and activities for women.

The book features also two other images of “Maidens of Finland”, besides the cover illustration, young women in a Finnish national garb, which at the wartime gained special symbolic significance. The women were considered to be the moral backbone of Finnish society, mothers and maiden Madonna who represented the national purity of Finnish morale.87 The relationships of Finnish women and German soldiers stationed in Finland were a not at all welcomed consequence of interactions during the war, and the women involved in these relationships had symbolically disappointed the entire Finnish nation.88 In the context of war, on the one hand, the masculinity of the nation was the primary representation and women were subordinated to the role of “the Other” as less significant for the representation of a manly, martial state. The “othering” of women in Das ist Suomi mirrors the changing values of the state. Prior to the war, women were altogether absent in some of the official imagery, such as stamps.89 Yet just a few years after the war, in the 1951 edition of Das ist Suomi,90 women are presented as more active in the worlds of work, sports, arts and nature, and also boys are being taught domestic skills. The soldiers have been faded out and more images of women and children appear in general. The war prompted discussions about the gender roles and seems to have levelled the differences between men and women within a relatively short time frame.91

In addition to Marshall Mannerheim, the only portraits shot from a personally close distance and with their gazes meeting the viewer are those of the writers Maila Talvio and V. A. Koskenniemi. They were some of the most prominent advocates of the Finnish-German cultural relations, well-known in Germany, and to some degree even sympathetic with the national-socialist regime (Figure 8).92 They seem to have been chosen as personal mediators between the Finnish and German audiences in this publication as well. Maila Talvio actually seems to be wearing a brooch resembling a stylized swastika. Curiously enough, the same image of Talvio features in her 1953 book titled “Selected writings” but the brooch has been framed out, perhaps signaling the new political atmosphere and the pro-Soviet mentality of the 1950s.93 Nearly all the artists and cultural people illustrated in this book conform to the friendly relations of Finns and Germans, and the context of war seems to have narrowed down the scope of illustrated artists considerably. In contrast, in the 1951 edition of the book the coverage is much more varied. Cultural exchange played an important role in crafting ideological unity between the two countries prior to and during the war.94

Partisan in the printing house

Although aimed for the popular audience, Das ist Suomi is propaganda-oriented in its themes, similar to the other Finnish wartime books aimed for the German market.95 The Finnish war aims are subtly yet firmly touched upon in the illustrations and captions. However, the book also features one interesting, clandestine example of expressing contradictory political motives.

Somewhere along the book production process someone managed to tamper with and retouch one photo in the book, to present pro-Soviet counter-propaganda. Across the upper part of an image of the Seikku sawmills’ factory hall in Pori, is scribbled a text in Russian: “да здравствует карело-финская советская социалистическая республика!” (“Long live the Karelian-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic!”). This is done in a relatively covert manner, almost in a way that it looks like a banner stretching across the factory hall. On a quick browsing this text passes easily without noticing, which was probably also the writer’s intention.

This presents a curious pro-Soviet partisan act in a print product aimed for the Nazi German public, carried out by some supporter of the Soviet efforts working within the Finnish book industry. The underlying national tensions, hidden behind the rhetoric of a “unifying war”, became clearly visible in this act. There were internal political tensions, and also pro-Soviet feelings, in Finland during the war. These became expressed, for instance, by the activities of so-called “desants”, infiltrated spies from the Soviet Union, and the Soviet and Finnish spies working underground in Finland.96 However, the inclusion of a pro-Soviet slogan into a popular book aimed for the German public exemplifies a much subtler and, in our opinion, more thought-provoking, partisan propaganda act than the other activities of spies. To our knowledge this incident has not been discussed anywhere else, and we do not know of any other examples of analogous secretive activities. These kinds of examples of delicate propaganda acts could offer a fruitful research avenue of their own.

Conclusion

Das ist Suomi represents a photographic example of Finnish wartime propaganda aimed for the German public. There are unique characteristics to this book that are obvious attempts to please the German audience, and propaganda-laden sections specific to wartime, such as images of the destroyed landscapes of Karelia. The book shows an interesting compilation covering basically all the trends prevalent in the Finnish national imagery up to WW2, from the scenic landscapes of 19th century national awakening, to the military camp mentality of 1930s.97 An elitist view, evident in the portrayal of landscapes and people, is a tendency familiar in nationalistic representations that aim to craft an ideal and unified nation state, in essence a created and illusory community.98 However, the partisan act of including a pro-Soviet slogan clandestinely into the book undermines the imagined unity and wholeness of this community.

Finns are illustrated in the book as having ancient historical roots that include just the right amount and right kind of primitive folkways, as shown by the emphasis on the Karelian folk culture. In this kind of agrarian nationalistic perspective, the ethnographic details capitulate for a romantic presentation of racially pure and healthy rural “type figures”.99 Then again, the Sámi of the north are essentially represented as a stereotypical colonialist “Other”,100 although not as strongly as in the post-war editions of the book,101 which mirror the changes in the state’s political attitudes and economic involvements in northern Finland.

The book represents an idealized view of especially the Finnish man, an illustration which culminates in its final chapter ”The Finnish Soldier”. According to Andreas Ahlbäck, an idea of the mandatory military service as a modernizing force for Finnish men existed in the inter-war period. Ideally these men retained a connection to “the spirit of the forefathers” and their rural origins, but became useful, patriotic and – if you will – real men in the army.102 Men were forged in the wartime context into a narrow role emphasizing their manhood as the protectors of the fatherland,103 as is evident also in the numerous presentations of athletes and soldiers in the book.

However, WW2 shook strongly the traditional gender roles in Finland, as also elsewhere.104 This becomes evident in the post-war editions of the book, where women are represented in more active roles, also outside the private sphere.105 Although women gained new agency through the various work and aid activities prior to the war and during it, for instance, by performing what had been previously men’s work in factories,106 they were still apparently seen as passive receivers of male protection.107 Women were also considered to carry a moral responsibility in the society, in contrast to the martial duties of men.108

Visual representation is a very persuasive way to communicate the idealized versions of history. Also, the chosen captions illustrate the ways in which certain meanings in images can be distorted, blurred or coaxed for specific purposes, for instance, for maintaining canonized views of nationhood – many of which are in fact still being maintained. In contrast to the images themselves, the figure captions in this book convey propagandistic messages that in many cases even contradict the stereotypically represented sceneries. This brings to the general description a martial bend related to the wider WW2 context. Das ist Suomi permits a glimpse at a very particular period, and at how that affected the public presentation of Finland to the German co-belligerents.

Tuuli Koponen is a PhD candidate in archaeology at the University of Oulu, Finland. Her research focuses on the representation and commemoration of WW2 in Finland, with a particular interest in wartime photography.

Oula Seitsonen is an archaeologist and geographer at the University of Helsinki, Finland, with a wide range of interests ranging from prehistoric pastoralism to contemporary archaeology. He is currently working as a postdoctoral researcher in the project Lapland’s Dark Heritage on the materiality of Hitler’s Arctic war.

Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto is a postdoctoral researcher of ethnology at the University of Jyväskylä. She is an ethnographer and folklorist who have studied the engagements with WW2 heritage in Finnish Lapland, including history hobbyists’ activities, museums exhibitions, memorials, cemetery tourism, and oral histories.

Bibliography

Adelman, Jeremy & Aron, Stephen. From borderlands to borders: Empires, nation-states, and the peoples in between in North American history. The American Historical Review 104:3 (1999), 814-841.

Ahlbäck, Anders. Manhood and the Making of the Military: Conscription, Military Service and Masculinity in Finland, 1917-39. Ashgate Publishing Limited, Farnham, Surrey, England 2014.

Auer, Väinö (ed.). Anteil der finnischen Forscher an der Erforschung von Kola, Ostkarelien und Ingermanland. Fennia 67:3 (1942).

Auer, Väinö & Jutikkala, Eino. Finnlands Lebensraum. Das geographische und geschichtliche Finnland. Metzner, Berlin 1941.

Bell, Philip. Content Analysis of Visual Images. In Theo van Leeuwen & Carey Jewitt (ed.), Handbook of Visual Analysis. Sage, London 2001, 10-34.

Fewster, Derek. Visions of Past Glory. Nationalism and the Construction of Early Finnish History. Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki 2006.

Fingerroos, Outi: Karelia: A Place of Memories and Utopias. Oral Tradition 23:2 (2008), 235-254.

Haapanen, Atso. Viholliset keskellämme. Desantit Suomessa 1939-1944. Minerva, Helsinki 2012.

Hall, Stuart. Identiteetti. (translated by Lehtonen, Mikko & Herkman, Juha) Vastapaino, Tampere 1999.

Harjula, Mirko. Venäjän Karjala ja Muurmanni 1914-1922. Maailmansota, vallankumous, ulkomaiden interventio ja sisällissota. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 2007.

Hautala-Hirvioja, Tuija. Frontier Landscape – Lapland in the Tradition of Finnish Landscape Painting. Acta Borealia 28:2 (2011), 183-202.

Hautala-Hirvioja, Tuija. Lappi-kuvan muotoutuminen suomalaisessa kuvataiteessa ennen toista maailmansotaa. Jyväskylän yliopisto, Jyväskylä 1999.

Holmila, Antero & Mikkola, Simo. Suomi sodan jälkeen. Pelon, katkeruuden ja toivon vuodet 1944-49. Atena, Jyväskylä 2015.

Honkaniemi, Marika. Taistelusta taiteeksi. Tiedotuskomppanioiden valokuvat Ateneumin suomalais-saksalaisessa Taistelukuvaajain näyttelyssä 1942. Sigillum, Turku 2017.

Häyrynen, Maunu. Kuvitettu maa. Suomen kansallisen maisemakuvaston rakentuminen. Suomalainen kirjallisuuden seura, Helsinki 2005.

Hytönen, Kirsi-Maria & Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika. Johdanto: miehet ja naiset suomalaisessa palkkatyössä ja sen tutkimuksessa. In K-M. Hytönen & E. Koskinen-Koivisto (ed.) Työtä tekee mies, nainen. Väki Voimakas 24. Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura, Tampere 2010, 7-23.

Hytönen, Kirsi-Maria. Ei elämääni lomia mahtunut. Naisten muistelukerrontaa palkkatyöstä talvi- ja jatkosotien jälkeen ja jälleenrakennuksen aikana. Joensuu, Suomen Kansantietouden Tutkijain Seura 2014.

Jewitt, Carey & Oyama, Rumiko. Visual Meaning: A Social Semiotic Approach. In Theo van Leeuwen & Carey Jewitt (ed.) Handbook of visual analysis. Sage, London 2001, 134-156.

Jewitt, Carey. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. Routledge, London 2009.

Jokinen, Arto. Myytti sodan palveluksessa. Suomalainen mies, soturius ja talvisota. Teoksessa: Tiina Kinnunen & Ville Kivimäki (ed.) Ihminen sodassa. Suomalaisten kokemuksia talvi- ja jatkosodasta. Minerva, Helsinki 2006, 141-157.

Jokisipilä, Markku. Napapiirin aseveljet. In Robert Alftan (ed.) Aseveljet. Saksalais-suomalainen aseveljeys 1942-1944. WSOY, Juva 2005, 9-51.

Jokisipilä, Markku & Könönen, Janne. Kolmannen valtakunnan vieraat. Suomi Hitlerin Saksan vaikutuspiirissä 1933-1944. Otava, Keuruu 2013.

Jonasson, Felix (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i bilder. Finland in pictures. Finnland in Bildern. WSOY, Porvoo 1929.

Jonasson, Felix (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i bilder. Finnland in Bildern. Finland illustrated. Finlande pittoresque. WSOY, Porvoo 1930.

Jonasson, Felix (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i bilder. Finnland in Bildern. Finland illustrated. Finlande pittoresque. Finlandia pintoresca. WSOY, Porvoo 1934.

Kananen, Heli Kaarina. Kontrolloitu sopeutuminen. Ortodoksinen siirtoväki sotien jälkeisessä Ylä-Savossa (1946-1959). Jyväskylän yliopisto, Jyväskylä 2010.

Kemiläinen, Aira. Finns in the Shadow of the ”Aryans”: Race Theories and Racism. Helsinki: Finnish Historical Society, 1998.

Kemppainen, Ilona. Isänmaan uhrit. Sankarikuolema Suomessa toisen maailmansodan aikana. Bibliotheca Historica 102. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2006.

Kirves, Jenni & Näre, Sari. Nuorten talkoot: isänmaallinen työvelvollisuus. In Sari Näre, Juha Siltala & Jenni Kirves (ed.) Uhrattu nuoruus. Sodassa koettua 2. Weilin+Göös, Porvoo 2008, 64-87.

Kleemola, Olli. Lapin maisemia ja tuhottuja kirkkoja – valokuvapropaganda Suomesta ulkomaille 1939-1944. In Virpi Kivioja, Olli Kleemola & Louis Clerc (ed.) Sotapropagandasta brändäämiseen: Miten Suomi-kuvaa on rakennettu. Docendo, Jyväskylä 2015, 100-123.

Kleemola, Olli. Valokuva sodassa. Neuvostosotilaat, neuvostoväestö ja neuvostomaa suomalaisissa ja saksalaisissa sotavalokuvissa 1941-1945. Sigillum, Turku 2016.

Kormano, Riitta. Amputoidun maan pirstoutuneet puut. Sotamuistomerkkien luontosymboliikka sisällissodan punaisten ja luovutetun Karjalan uhrien muiston välittäjänä. In Tiina Kinnunen & Ville Kivimäki (ed.) Ihminen sodassa: suomalaisten kokemuksia talvi- ja jatkosodasta. Minerva, Helsinki-Jyväskylä 2006, 279-295.

Korpi, Kalle. Rintama ilman juoksuhautoja. Saksalaisten keskeiset rakentamiset, työmaat ja työvoima Pohjois-Suomessa 1941-1942. Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen yhdistys, Rovaniemi 2010.

Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika. A Greasy-Skinned Worker. Gender, Class and Work in the 20th-Century Life Story of a Female Labourer. University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä 2013.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. Routledge, London 1996.

Laitila, Inka-Maria. Puistojen kaupunki, Hämeenlinnan vanhojen puistojen historiaa ja puistokulttuuria. Hämeenlinnan kaupungin historiallinen museo, Hämeenlinna 1995.

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka. Saamelainen evakko. Rauhan kansa sodan jaloissa. City Sámit, Helsinki 1994.

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka. Lappalaiskaravaanit harhateillä, kulttuurilähettiläät kiertueella? Saamelaiset Euroopan näyttämöillä ja eläintarhoissa. Faravid 33 (2009), 321-346.

Lehtola, Veli-Pekka. Second World War as a Trigger for Transcultural Changes among Sámi People in Finland. Acta Borealia 32:2 (2015), 125-147.

Lintonen, Kati. Valokuvallistettu luonto. I. K. Inhan tuotanto luonnon merkityksellistäjänä. Unigrafia, Helsinki 2011.

Lukkarinen, Ville. & Waenerberg, Annika. Suomi-kuvasta mielenmaisemaan. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, Helsinki 2004.

Lönnqvist, Bo 1978. Kansanpuku ja kansallispuku. Helsinki: Otava.

Naum, Magdalena. Between Utopia and Dystopia: Colonial Ambivalence and Early Modern Perception of Sápmi. Itinerario 40:3 (2016), 489-521.

Nordqvist, Kerkko & Seitsonen, Oula. Finnish Archaeological Activities in the Present-day Karelian Republic until 1944. Fennoscandia Archaeologica XXV (2008), 27-60.

Ollila, Anne. Suomen kotien päivä valkenee… Marttajärjestö suomalaisessa yhteiskunnassa vuoteen 1939. Historiallisia tutkimuksia 173. Suomen Historiallinen Seura, Helsinki 1993.

Paasi, Anssi. Territories, boundaries and consciousness. The changing geographies of the FInnish-Russian border. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester 1996.

Pimiä, Tenho. Sotasaalista Itä-Karjalasta. Suomalaistutkijat miehitetyillä alueilla 1941-1944. Ajatus, Helsinki 2007.

Poikonen, Jaakko. Suur-Suomea perustamassa? Poleemi 4/2006 (2006), 24-28.

Prusin, Alexander. The Lands Between. Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 1870-1992. Oxford University Press, New York 2010.

Pälsi, Sakari. Petsamoon kuin ulkomaille. Otava, Helsinki 1931.

Raivo, Petri. Maiseman kulttuurinen transformaatio. Ortodoksinen kirkko suomalaisessa kulttuurimaisemassa. Department of Geography, University of Oulu, Oulu 1996.

Rislakki, Jukka. Maan alla: Vakoilua, vastarintaa ja urkintaa Suomessa 1941-1944. Love 1986.

Rose, Gillian. Visual methodologies. An introduction to researching with visual materials. 4th edition. SAGE Publications Ltd, London 2016.

Saarikoski, Kirsi. Puu, metsä ja luonto. Arkkitehtuuri suomalaisuuden rakentamisena ja rakentumisena. In Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen (ed.) Suomi. Outo pohjoinen maa? Näkökulmia Euroopan äären historiaan ja kulttuuriin. PS-Kustannus, Porvoo 1999, 166-207.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. Pantheon, New York 1978.

Seitsonen, Oula. Digging Hitler’s Arctic War: Archaeologies and Heritage of the Second World War German Military Presence in Finnish Lapland. Unigrafia, Helsinki 2018.

Seitsonen, Oula & Koskinen-Koivisto, Eerika. “Where the F… is Vuotso”: Heritage of Second World War forced movement and destruction in a Sámi reindeer herding community in Finnish Lapland. International Journal of Heritage Studies 24:4 (2017), 421-441.

Seitsonen, Oula, Koponen, Tuuli & Herva, Vesa-Pekka. ”Lapland’s Roadway”: German photography and experience of the European far North in the Second World War. Submitted to Photography and Culture forthcoming (2018).

Seppänen, Janne. Visuaalinen kulttuuri: teoriaa ja metodeja mediakuvan tulkitsijalle. Vastapaino, Tampere 2005.

Skjöldebrand, Anders Fredrik. 1805. Voyage pittoresque au Cap Nord. Chez Charles Delén, Stockholm.

SMY, Muinaista ja vanhaa Itä-Karjalaa. Tutkielmia Itä-Karjalan esihistorian, kulttuurihistorian ja kansankulttuurin alalta. Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Helsinki 1944.

Suikkari, Raimo. Finland. Design. Knowhow. Nature. RKS Tietopalvelu, Espoo-Helsinki 2012.

Summerfield, Penny. Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives. Discourse and Subjectivity in Oral Histories of the Second World War. Manchester University Press, Manchester 1998.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finnland in Bild und Wort. Das ist Suomi. WSOY, Porvoo 1943a.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Das ist Suomi. Finnland in Bild und Wort. Metzner, Berlin 1943b.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i ord och bild. WSOY, Porvoo 1944.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finnland in Bild und Wort. Das ist Suomi. WSOY, Porvoo 1946a.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland in pictures. WSOY, Porvoo 1946b.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland in pictures. WSOY, Porvoo 1947.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i ord och bild. WSOY, Porvoo 1949.

Suova, Maija (ed.). Suomi kuvina. Finland i ord och bild. WSOY, Porvoo 1951.

Urponen, Maija. Ylirajaisia suhteita: Helsingin olympialaiset, Armi Kuusela ja ylikansallinen historia. Helsingin yliopisto, Helsinki 2010.

Talvio, Maila, & V. A. Koskenniemi. Valitut Teokset. Porvoo: WSOY, 1953.

Valenius, Johanna. Undressing the maid. Gender, Sexuality and the Body in the construction of the Finnish Nation. The Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki 2004.

Vallas, Hannu & Heikkilä, Markku. Destination Finland. ÐÑÑÐ3/4Ñ,,Ð3/4Ñ,Ð3/4ÑÐ1/2иÐ1/4ки пейзажей. Aerial landscapes. Maisemat ilmakuvina. Kirjakaari, Helsinki 2014.

Vallius, Antti. Kuvien maaseutu. Maaseutumaisemakuvaston luomat mielikuvat suomalaisesta maaseutukulttuurista. Jyväskylän yliopisto, Jyväskylä 2013.

Virtanen, Pekka. Metsä antaa mitä metsällä on. In Tero Halonen & Laura Aro (ed.) Suomalaisten symbolit. Atena, Jyväskylä 2005, 49-53.

Westerlund, Lars. Saksan vankileirit Suomessa ja raja-alueilla 1941-1944. Tammi, Helsinki 2008.

Worthen, Hana. Playing “Nordic”: The Women of Niskavuori, Agri/culture, and Imagining Finland On the Third Reich Stage. University of Helsinki, Helsinki 2007.

YLE. Miss Europe Sirkka Salonen in the interview. September 15 1938. Interviewer Alexis af Enehjelm. Yleisradio 1938, https://yle.fi/aihe/artikkeli/2006/09/08/sirkka-salonen-miss-suomi-1938 (1.1.2018).

Ylimaunu, Timo. Postimerkit ja identiteetti – kuva suomalaisesta yhteiskunnasta 1930-luvulta. Tabellarius 7 (2005), 84-101.

Ylimaunu, Timo & Koponen, Tuuli. Hävitettyä ja luotua materiaalista muistia. Näkökulma eräisiin SA-valokuviin Jatkosodan Karjalasta. SKAS 1/2017 (2017), 15-37.

- e.g. Hentilä & Hentilä 2017. [↩]

- e.g. Suova 1943a-b; Mabre 1943-1944; Wehrmacht 2006 [1943]; Seitsonen et al. forthcoming. [↩]

- e.g. Fewster 2006, 50. [↩]

- Manninen 1980, 49; Laine 1993, 97, 106; Poikonen 2006; Nordqvist & Seitsonen 2008. [↩]

- Jutikkala 1941. [↩]

- Jaakkola 1941. [↩]

- Auer 1942. [↩]

- SMY 1944. [↩]

- Suova 1943a-b. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005; Ylimaunu 2005. [↩]

- Valenius 2004. [↩]

- Kleemola 2015, 2016; Honkaniemi 2017. [↩]

- e.g. Ylimaunu & Koponen 2017. [↩]

- e.g. Bell 2001, 10-34; Seppänen 2005: 142-176; Rose 2016, 85-105. [↩]

- e.g. Kress & van Leeuwen 1996; Jewitt & Oyama 2001, 134-156; Seppänen 2005, 90-93; Jewitt 2009. [↩]

- Jonasson 1929, 1930, 1934. [↩]

- Suova 1943a-b, 1944, 1946a-b, 1947, 1949, 1951. [↩]

- Suova 1943a. [↩]

- Suova 1943b. [↩]

- e.g. Suikkari 2012; Vallas & Heikkilä 2014. [↩]

- Laitila 1995. [↩]

- Kleemola 2015, 104-105; 2016, 40, 228, 232-236; Honkaniemi 2017, 120-121 [↩]

- Meinander 2012, 76; Airio 2014, 265-266. [↩]

- see Pimiä 2007. [↩]

- Fingerroos 2008. [↩]

- e.g. Harjula 2007. [↩]

- Ylimaunu 2005, 98; Fewster 2006. [↩]

- Suova 1946b. [↩]

- e.g. Reitala 1983; Valenius 2004. [↩]

- Reitala 1983, 11, 19. [↩]

- Reitala 1983, 87-88. [↩]

- Hall 1999, 46-47. [↩]

- Valenius 2004. [↩]

- Hall 1999, 54. [↩]

- Valenius 2004. [↩]

- Lönnqvist 1978. [↩]

- Kemiläinen 1998; Häyrynen 2005, 140. [↩]

- Reitala 1983, 134. [↩]

- YLE 1938; Reitala 1983, 134. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 41. [↩]

- e.g. Reitala 1983; Häyrynen 2005. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 9. [↩]

- Raivo 1996, 119; Häyrynen 2005, 74. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 39. [↩]

- Virtanen 2005, 51. [↩]

- see Häyrynen 2005. [↩]

- Lintonen 2011, 82; also Suova 1951. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 171. [↩]

- e.g. Adelman & Aron 1999. [↩]

- Prusin 2010; Jokisipilä & Könönen 2012, 38; Pilke 2015, 85-89. [↩]

- Paasi 1996, 112, Häyrynen 2005, 176. [↩]

- Raivo 1996, 129-130. [↩]

- Kormano 2006, 280, 286; Kleemola 2014, 34-36. [↩]

- Lukkarinen & Waenerberg, 2004, 13-14; Hautala-Hirvioja 2011, 188. [↩]

- Seitsonen et al. forthcoming. [↩]

- Seitsonen et al. forthcoming. [↩]

- Herva 2014; Naum 2016; Seitsonen et al. forthcoming. [↩]

- Skjöldebrand 1805. [↩]

- Hautala-Hirvioja 1999, 34. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 41. [↩]

- e.g. Korpi 2010; Seitsonen 2018; Westerlund 2008. [↩]

- Hautala-Hirvioja 2011, 195. [↩]

- Jewitt & Oyama 2001, 135-136 [↩]

- Suova 1951. [↩]

- Lehtola 2015; Seitsonen 2018, 147-148. [↩]

- Lehtola 1994, 191-224, 2015; Keskitalo et al. 2014; Puuronen 2014, 322. [↩]

- Ylimaunu 2005, 101. [↩]

- Lehtola 2009; Seitsonen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2017. [↩]

- Raivo 1996, 118-133. [↩]

- e.g. Kananen 2010. [↩]

- Pälsi 1931. [↩]

- Saarikangas 1999, 187. [↩]

- Saarikangas 1999, 168-169, 187. [↩]

- Ylimaunu 2005, 94; Saarikangas 1999, 183. [↩]

- See Ylimaunu 2005, 96. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 124. [↩]

- Kormano 2013: 280-281. [↩]

- Also Ylimaunu 2005, 98; Raivo 2005, 143. [↩]

- Ylimaunu 2005, 98; Fewster 2006, 321. [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 161. [↩]

- Kemppainen 2006. [↩]

- Kleemola 2016: 148-150. [↩]

- Jääskeläinen 1998, 58; Ylimaunu 2005, 97-99. [↩]

- Paavolainen 1938, 289 (our translation). [↩]

- e.g. Hytönen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2010. [↩]

- Ollila 1993. [↩]

- Paasi 1996, 153; Jokisipilä 2005, 48. Kemppainen 2006. [↩]

- Junila 2000, 277; Urponen 2010; Kinnunen & Jokisipilä 2012, 477. [↩]

- Ylimaunu 2005, 100-101. [↩]

- Suova 1951. [↩]

- Holmila & Mikkonen 2015, 119-123; also Ylimaunu 2005, 101. [↩]

- Jokisipilä & Könönen 2013. [↩]

- Talvio & Koskenniemi 1953. [↩]

- Worthen 2007; Jokisipilä & Könönen 2013. [↩]

- Auer & Jutikkala 1941; Jaakkola 1941; SMY 1944. [↩]

- e.g. Rislakki 1986; Haapanen 2012. [↩]

- see Häyrynen 2005; also Vallius 2013. [↩]

- Anderson 1991; Jääskeläinen 1998, 58; Häyrynen 2005, 29; Ylimaunu 2005, 97-99 . [↩]

- Häyrynen 2005, 161; also Vallius 2013. [↩]

- Said 1978; Seitsonen 2018, 70-71. [↩]

- Suova 1951. [↩]

- Ahlbäck 2014, 231-244. [↩]

- Jokinen 2006. [↩]

- Summerfield 1998, 45. [↩]

- Suova 1951. [↩]

- Kirves & Näre 2008, 66-68; Hytönen & Koskinen-Koivisto 2010; Koskinen-Koivisto 2013, 78; Hytönen 2014. [↩]

- Alhbäck 2014, 232. [↩]

- e.g. Kemppainen 2006; Urponen 2010. [↩]